Agriculture and Food Production in the Shadow of the Arab Oil Economy

Amman, January 28-29th 2012

In ever more alarming terms over the past decade, international organisations have documented shortfalls in food production and hence in the ‘food security’ of populations of the Arab region. Their reports indicate clearly that the region has the greatest food ‘deficit’ of any region of the world. However valuable such reports are in conveying a sense of the global problem, they are necessarily restricted in analysis to existing statistical sources, notably those produced by government agencies, and in prescription to the international normative consensus on economic policy. As university-based researchers, however, we were able to go behind the statistics to document the problems of productivity and livelihood in rural societies across the region, bringing together in discussion perspectives often kept apart – those of agronomists, anthropologists, economists, health scientists and geographers. As academics, moreover, in debate over policy matters we are not shackled by today’s economic normative consensus.

Papers in the workshop addressed the following issues: the relation between large-scale capitalized agriculture and small-scale domestically managed food-production, and between irrigated and rain-fed agriculture; the articulation and conditions of work across different sectors; land-use (and landscape) between building construction, speculation and food-production in markets fuelled by oil-rent; the impact of the resulting land-use on both animal herders and farmers; and economic and legal policies at regional, national and local levels as they determine the capacity of societies to produce food. Research analyses concern Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Syria, Tunisia and Yemen.

In the course of the two day workshop similar patterns emerged across the countries: the impoverishment of rural livelihoods and the polarization of the agricultural sector between capitalized production (increasingly of vegetables and fruits) and the declining production of grains and pulses that has developed sharply over the last quarter century of neo-liberal economic policy. A series of documentary films were also screened during the workshop.

Below is a report on the workshops and detailed abstracts of the specific papers presented. We are grateful to The British Academy (workshop funding from the Middle East and North Africa Panel and small research grant SG102312) and the London School of Economics (further support from the Research Committee, Middle East Centre and Anthropology Department) for their support. The workshop would not have been possible without the excellent work of Carol Palmer and Nadja Qaysi at CBRL British Institute Amman, Dr Kamil Mahdi and Ms Elizabeth Saleh helping in the organisation and summing up of the workshop

Participants and audience

The two short days were intense with 23 paper-givers presenting. There were a number of Jordanian colleagues who either chaired sessions or attended the workshop, but it was essentially a working meeting of those presenting papers.

It is noteworthy that the paper presenters comprised both senior (Kishk, Othman, Hakimi, Zurayk, Ayeb, Palmer, Taminian, Saleh, Chatty, Ghafour, Elloumi, and Kadri) and junior (Sarkis-Fernandez, Habib, Pelat, Tesdell, Foy, Gharaibeh, Riachi, Eid-Sabbagh, Ababsa) scholars, and academics and practicing agronomists (Pelat, Bakri). Yet there emerged a common critical understanding of the sector and an enthusiasm to continue working together.

The sessions addressed the following topics:

The deepening capitalist transformation of agrarian relations: land and food

High-price agriculture

Transmitting knowledge and cultivars

Documenting long-term agrarian transformation

Water rights and markets (1) national systems

Water rights and markets (2) irrigation systems

Investment of oil rent: the landscapes of pastoralists and farmers

Responses: macro and micro

Below are the detailed abstracts of the papers presented at each session:

Session 1: The deepening capitalist transformation of agrarian relations: land and food

Hassanein Kishk, National Centre for Sociological and Criminological Research, Cairo –

تدهور أنماط الغذاء لدى الفلاحين الفقراء والعمال الزراعيين المعدمين فى الريف المصرى :الآليات والنتائج

تتضمن الورقة خمسة أقسام هى:

1 مقدمة حول موضوعها، وتعريف لأهم المفاهيم المستخدمة فيها، مثل الفلاحون )الفقراء والصغار)، والعمال الزراعيون المعدمون، والرأسماليون الزراعيون (المتوسطون والكبار)، والأسرة المعيشية، وأشكال إعادة إنتاج الوجود الاجتماعى. وتتضمن المقدمة التساؤلات الثلاثة الرئيسية التى تسعى الورقة إلى الإجابة عليها وهى: ماذا ولماذا وما هى أشكال مواجهة ماحدث ويحدث لأنماط الغذاء لدى الفلاحين الفقراء والعمال الزراعيين المعدمين. كما تتضمن أيضاً منهجية الإجابة عن تلك التساؤلات.

2- إشارة موجزة لدور كل من الشركات دولية النشاط المنتجة للسلع الغذائية، والسياسة الاقتصادية النيوليبرالية، التى تنتهجها الدولة المصرية، فى الارتفاع المستمر لأسعار الغذاء.

3- نتائج ذلك على أنماط الغذاء لدى أفقر فقراء الريف المصرى. وذلك من واقع البيانات الكلية (الماكرو)، أو الجزئية (المايكرو) والمتمثلة فى نتائج البحوث الميدانية التى أجريت منذ السبعينات من القرن العشرين وحتى عام 2011.

4- الأشكال التى يواجه بها الفلاحون الفقراء والعمال الزراعيون تلك النتائج، وذلك على المستويين الكلى والجزئى. وهى أشكال إعادة إنتاج الوجود الاجتماعى لهم، والتى يطلق عليها البعض استراتيجيات البقاء.

5- خاتمة حول المواجهة المنظمة وأدواتها، مثل اتحادات الفلاحين ونقابات العمال الزراعيين وبعض الأحزاب السياسية التى بدأت فى الوجود فى أعقاب ثورة 25 يناير 2011، وهى التنظيمات المستقلة عن سيطرة الدولة والتى تتبنى برامج سياسية واقتصادية تعمل ضد الاحتكارات العالمية وأتباعها المحليين، وضد الرأسمالية المصرية.

Abdo Ali Othman, Sociology Department, University of Sanaa –

نماذج من انماط التغيرات والعلاقات الزراعيه المحليه في اليمن

الاهداف

مناقشة انماط العلاقات والتغيرات في العلاقات الزراعية المحلية في اليمن وخاصة خلال العقود الثلاثة الاخيرة

التحول من الاقتصاد المعاش الى اشكال حديثة من العلاقات الزراعية ومارافق ذلك من تدهور في مزارع المنتجين الصغار وخاصة في انتاج الغذاء الاساسي.وانتشار زراعة القات ليحل محل زراعة الحبوب

التركيز في المناطق المدروسة على النشاط الاقتصادي للسكان ,وادارة الموارد الموارد الطبيعية ( الارض والمياه, والمراعي ) وشبكة العلاقات الاجتماعية(الراسمال الاجتماعي)

معرفة تاثير المؤسسات التقليدية والحديثة في عملية التحديث الذي اوجدته بعض الفئات وماترتب على ذلك من عدم التوازن في عملية التنمية الاجتماعية والاقتصادية محليا ودورها في انتشار الفقر وهجرة المزارعين من الريف الى المدن بحثا عن الاعمال وخاصة العمال الهامشية

القات

يرى بعض الخبراء ان التوسع في زراعة القات احد الاسباب في تدني قدرة القطاع الزراعي على تحقيق الاكتفاء الذاتي من المحاصيل الزراعية والحبوب وكذا التقليل من نسبة الفجوة الغذائية الواسعة بين الانتاج والاستهلاك

انفاق الاسرة على شراء القات يصل الى 26 – 30% من دخل الاسرة ويحتل المرتبة الثانية بعد الغذاء مما يشكل عبىء على ذوي الدخل المحدود

:الجماعات الاجتماعيه المحلية

الجماعات الاجتماعية المحليه في اليمن هي : الفلاحون , رجال الدين , التجار ,الحرفيون, والجماعات الفقيره من الهامشيين

هناك من ينظر الى الفئات والطبقات الاجتماعية في اليمن من خلال تقسيم العمل الاجتماعي. وتتكون البنية الاجتماعية لديهم من كبار ملاك الارض, الفلاحين و الاغنياء , التجاروالمقاولين, متوسطو التجارواصحاب الملكيات الزراعية المتوسطة ,الموظفين , المثقفين, الفلاحين الفقراء, الحرفيين واخيرا العمال بما فيهم الجماعات الهامشية

:وصف الجماعات المحلية ومصادر الثروة الطبيعية في مناطق الدراسة

:قرية حضران

وتظم حضران, بيت مهدم وبيت ضالعه وتقع في بني مطر التابعة لمحافظة صنعاء وتبعد 70 كيلومتر عن مدينة صنعاء

يبلغ عدد السكان في القرى الثلاث حوالي 3200 نسمة وعدد الاسر تصل الى 330 اسرة

المحاصيل الزراعية في حضران :القمح ’ الشعير ’الذرة ’ البن والقات

مصادر المياه:الامطار , الابار والينابيع

20% من الاراضي الزراعية تستخدم مراعي للاغنام والابقار والارض المزروعة بالمحاصيل 300 الف لبنة

:قرية المسيال والمراميد

وتقع في مديرية بني سعد في محافظة المحويت وتتبع القريتان عزلة بني حمادي ويصل عدد السكان 750 نسمه ويشكلون 125 اسرة , ومعظم سكان القرى من الفقراء وكثير منهم فلاحون شركاء ويحصلون على اقل من ثلث المحصول وقد يصل الى الخمس.

المحاصيل الزراعية : الدخن والذرة الحمراء وتشكل ثلث المساحة وتعتمد على مياه الامطار والابار وتستخدم مساحة من الارض مراعي للاغنام والماعز والابقار.

منطقة الحامي

وهي منطقة شبه حضرية (بلده)وتقع الحامي في مديرية الشحر-محافظة حضرموت , عدد سكانها 8300 نسمه وعدد اسرها 1164

المحاصيل الزراعية : البطاط الحلو , البصل ,العلف والتبغ ثم الاسماك وتتمثل مصادر المياه في الامطار والمعيان والحمى

يراس كل عائلة كبيره مسؤول يسمى المقدم او الشيخ وتسمي اسر الساده رؤسائها ”المناصب“ ومفردها (منصب)

القرى المحيطة بالحامي ”رعوية ” وتسمى المناطق التي يسكنها الرعاه اهل الضرع في مقابل مناطق اهل الزرع ويمكن تسمية اهل البحر مناطق الصيد البحري

عموما تتسم الانشطة الاقتصادية للمجتمعات المحلية الثلاث بسمات مشتركه: الارض الزراعيه , مصادر المياه, وهناك موارد اخرى مثل تربية النحل والصيد البحري في حضرموت. تصل نسبة الارض المزروعة بالقات حوالي 80% في حضران و 10 %للبن و10 % للمنتجات الزراعية الاخرى

Amin Al Hakimi, YASAD and Faculty of Agriculture, University of Sanaa –

الزراعة المطرية في المرتفعات اليمنية وتأثيرات الاقتصاد النفطي العربي

Session 2: High-price agriculture

Anne Gough and Rami Zurayk, Interfaculty Graduate Environmental Sciences Program, American University of Beirut – Cut flowers and strawberries: agricultural control in Gaza

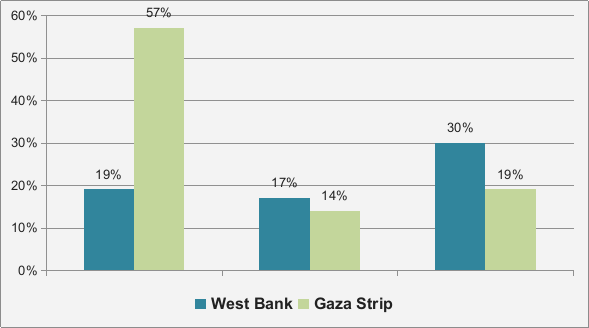

The agricultural sector in Gaza, Palestine, revolves around the export of highly perishable products such as strawberries and cut flowers. At the same time, 75% of people living in Gaza are considered food insecure or on the edge of food insecurity. There is a contradiction between an export industry supported by international development funding and a food insecure population dependent on food aid and living under Israeli occupation.

In this paper we examine how Gaza’s exports are produced within a pretext of Israel’s strategies to secure control over Palestinian land, resources, and people. While international aid agencies hope for stable access to export markets, Gaza’s dependence on Israeli food products and food aid increases.

We analyse the current situation and the formation of the current Gaza landscape through the lens of de-development (Roy 1987) and food regime theory (Friedmann 1993 and McMichael 2009). De-development is invaluable to any study of economic sectors, as it outlines how an occupying force can systematically undermine the development gains of populations. Food regime theory states that the study of food and agriculture offers insight into the global political economy and the function of food and land in spatial politics. These two political, economic and ecological theories assist in understanding the global and local power dynamics at play in Gaza’s imprisoned agricultural sector. The linkages between these two theories have rarely been explored.

The analytical framework is supported by data collection through a series of expert interviews in Gaza. We found that the role of commodity production in Gaza is an example of food regime theory’s concept of “niche production” (Friedman 1993) in which luxury goods like strawberries and cut-flowers are grown in poor countries in order that such goods are available in the global market place year-round. The goal was extolled as Palestinian economic development, but Israeli agricultural corporations quickly became involved as suppliers of inputs and mediators of export to Europe (Roy 2007). According to the Gaza Farmers’ Union almost of all of Gaza’s exports were handled through one Israeli company.

Much of our findings echo this contradictory example. A seemingly benign activity is in reality harmful to the Palestinian population and agricultural sector. We found this to be the case for agricultural extension, food imports and trade policy, and foreign aid.

We also found that the Israeli occupation has de-developed Gaza’s farming system through consistent violence levelled at farmers and agricultural landscapes. The persistent destruction of olive and other fruit tree orchards threatens to sever the economic and cultural connection between Palestinians and their land.

Today, Gaza is isolated and imprisoned by an occupying force. Gaza’s continual isolation must be challenged, as Palestine is pivotal in the regional struggle for autonomy and against authoritarian rule. Linking Gaza to global emancipatory and food sovereignty struggles while simultaneously resisting Israeli agricultural policies may be one way to subvert the oppressive control.

This paper draws on the findings of a study supported and conducted by the Institute of Palestine Studies. We are grateful for their assistance.

Diana Sarkis-Fernandez, Doctoral candidate, GER, University of Barcelona – Between growth and precariousness: working in Syrian greenhouses

The presentation analyzes the transformation of social relations of production and experiences of and on work in Syrian agriculture after the second infitah in the 1990s. For this purpose I focus upon the labor relations and workers’ live experiences in greenhouses in the Tartous region, where I have been doing ethnographic fieldwork between 2008 and 2010.

After a sketchy beginning in the end of the 1970s, the production of protected crops has spread after the 1990s, encouraged by the liberal economic policies of el-islah el-iqtisadi and tahrir el-suq. Between 1995 and 2008 the number of greenhouses in Tartous has passed from 31.600 to 127.478, and the greenhouse production has achieved a paradigmatic place in the development of the new successful economy. In macroeconomic terms the introduction of greenhouse protected crops has improved production, productivity and total production value (e.g. the production of tomatoes –the main protected crop in the country- went from 644.000 tons/35.000 Ha in 1980 to 1.166.000 tons/18.000 Ha in 2007, with a production value of nearly 9.933.235.000 LS and representing 55% of Syrian fruits and vegetable exports). At the ethnographic micro-level the introduction of protected crops has multiplied the profitability of the plots for the farmer-entrepreneurs (the production of aubergines and tomatoes provides 6 times more profits than the citrus production and 30 times more than the olive groves).

This process of « regional development » coincides with the hiring of seasonal migrant workers who come from the impoverished regions of Syria, are mostly hired on non-renewable temporary contracts and on a piece-rate type of remuneration (al-hissa) which reconfigures old forms of sharecropping . Within this context of agricultural modernisation for profitability and liberal economic reforms, this paper discusses the ways in which such workers are subjected to exploitative measures and how their subjection supports this successful regime of accumulation. The focus upon their experiences allows us to explore the following questions:

1) Which kind of capital-labour relations support this regime of food production? Which experiences of work and life sustain this structure of growth?

2) How do capital (the “market”) and the state regulate the production and reproduction of this informal structure of accumulation/dispossession/exploitation?

3) Which kind of moral and affective experienced economies support this informal structure of accumulation/dispossession/exploitation?

Furthermore this ethnographical case study led us to discuss the neoclassical economic theory, challenging two of its premises: 1) the assertion that automatically equates economic growth, productivity and profitability with social well-being; 2) the idea that the rule of the market implies the withdrawal of state regulation and of the other forms of social and moral embeddedness (in this sense I criticize the academic dichotomy between capitalist economy and moral and affective economies).

Therefore I defend the necessity to grasp the neoclassical theory as part of a hegemonic project about the economy which assures the dominance of capital over labour and the means of livelihood.

Rima Habib, Faculty of Health and Sciences, American University of Beirut – Health of farm workers: a social justice framework

The presentation offers a perspective drawing on research in Lebanon on the relationship between agricultural labour and health-related issues induced by such work practices. Farming labour is perhaps one of the most hazardous occupation and the region. Injuries include musculoskeletal disorders, reproductive health problems, pesticide exposure, respiratory problems and cancer. However they are subjugated to the peripheries of Arab society and with little access to health services. The paper explores the ways in which farmers are marginalized, making them dependent upon large landholders and quite often forced into migration. This needs to be understood within a wider context of capital-intensive agriculture. The case-study examined is from Lebanon.

Session 3: Transmitting knowledge and cultivars

Reem Saad and Habib Ayeb, Social Research Center, American University of Cairo – Gender, poverty and biodiversity conservation in rural Egypt and Tunisia

This paper investigates the links between poverty, gender and biodiversity in rural Egypt and Tunisia. The idea is to highlight women’s significant role in biodiversity conservation as well as the complexities that characterize the relationship between poverty and biodiversity protection. Despite natural and social diversity, Egypt and Tunisia are comparable in terms of their present paths of economic transformation. Agriculture and rural society are comparable in both countries in terms of scarcity of land and water, and threats to agricultural resources (urbanization, industrialization, tourism, and agro-investment… etc.). In both countries, rural dwellers are increasingly resorting to non-agricultural activity, including internal and external labour migration.

In both countries, liberalizing agricultural land and water markets has been a core component of the economic reform and structural adjustment policies. Those reforms have aggravated the problem of rural poverty, and had adverse impact on the general welfare and status of food security of a significant number of rural households. In both countries, the over-exploitation of agricultural resources and the introduction of new modes of farming (mainly the increasing reliance on hybrid seeds) are posing significant threats to agricultural biodiversity and to the ecological balance in general.

This problem has important implications for the welfare of rural dwellers especially due to the implications for food security. This paper aims at testing a hypothesis supported by research evidence from other world regions, that women’s increased access to secure land tenure and other agricultural resources is positively correlated with biodiversity conservation. The paper shall also test the same correlation regarding poor farmers. Given that women and the rural poor are vulnerable and therefore risk-averse and less likely to adopt modern farming methods, the paper raises the question of whether “traditional” modes of farming are necessarily more “resource-friendly” and environmentally sound.

Frédéric Pelat, Agricultural Engineer – Agricultural knowledge transmission in Yemeni highlands: a problem among others?

Poor Yemeni farmers living in the highlands from tiny rain-fed farms have suffered a lot from the agricultural mutations affecting their country for several decades. Farmers have not lost only yields, lands and seeds but also much traditional knowledge. For socioeconomic reasons, the young generations are abandoning extensive farming in order to migrate to the cities and other rural areas where more profitable irrigated agriculture is practiced. Although apparently very rudimentary, ancestral techniques and practices are particularly well adapted to local environmental and climatic mountainous contexts where intensification attempts are either impossible or unsustainable. Insufficiently documented, knowledge’s vitality is firstly intimately linked to practices of rain-fed farming that rely massively on local genetic resources built up by generations of farmers throughout centuries. In a country where sharp changes in agricultural production in less than fifty years have depleted much of the natural resources while making impoverished populations highly dependent on imported food, long-lasting rain-fed farming is still a refuge and a livelihood for many families and this role could be enhanced in the current period of crisis. Knowledge restoration, enhancement and transmission could become an essential question for the generations to come. This paper will discuss these issues by building on concrete cases from the field.

Omar Tesdell, PhD candidate, Geography Department University of Minnesota – Staging environments: agriculture, science, and aid in the West Bank

This presentation explores agronomic and humanitarian interventions within the Israeli-Occupied Palestinian West Bank since 1967. First, it traces the complex relationship of agricultural science programs with local farmers. For example, the Israeli government began offering agricultural extension and veterinary services to Palestinian farmers in 1967. This enduring scientific interest in the farming and conservation practices of Palestinians over forty years interacted uneasily with local farmers and environmental groups. Second, the presentation explores the balance of humanitarian food aid and development aid to Palestinians to illustrate the relationship of both processes. Overall, the paper demonstrates the contested status of modern agricultural science and humanitarianism within the Arab world and its articulation with a shifting environmental and political landscape.

Session 4: Documenting long-term agrarian transformation

Roman-Oliver Foy, Doctoral Student, Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne University

Laboratoire UMR CNRS ENeC, Lecturer at the University of Orleans – Makane (North Syria) since the 1940’s: technical changes and agrarian revolutions, yet reproduction of agricultural practices and social Structures?

Maskane on the steppe plateau, west to the Tabqa Dam, is considered by some as a symbol of successful agricultural development. This is especially because of the semi-arid climates of eastern Syria. Yet drastic changes in the agrarian sector of Syria, which began in the 1940s, have completely altered the appearance of Maskane’s landscape. Agrarian reforms such as the mechanization of agriculture production, the creation (and dissolution) of state farms, and finally the redistribution of lands to nuclear families have resulted in shifts in the types of agricultural produce. For example since the completion of the irrigation infrastructure in the 1970s, local residents have been able to cultivate crops other than barley and wheat, such as cotton and sugar beets. Alongside such modifications through state policy, social restructuring appears to also have taken place. The first of these was when local residents, formerly share-croppers, were hired as farmers by the state farms. Following the abandonment of the collective state farms and the redistribution of lands to individual farmers and their families, another cycle of social transformation took place. This paper examines the ways in which the local population has adapted to such radical changes in the types of policies deployed by the state within such a short period of time.

The paper is based upon fieldwork conducted between September 2008 and August 2010. In addition to the collection and collation of archives and official statistics, I was able to conduct interviews with approximately 100 local residents. This methodology is particularly useful for such a context given that Syrian state policy which collectivized the lands, did not consider the inhabitants as individuals but instead as a homogeneous group. Hence, integrating qualitative research that includes discussions with locals allows for a wider understanding of the ways in which state strategies are understood and practiced. Interviewing took place with landowners, farmers, sharecroppers and state employees. Narratives offered especially by older residents offered insights into their experiences of the changes that took place across the region since the 1940s. Several individual testimonies also provided empirical evidence that could then be compared and contrasted with the statistical and official sources. The sum of these viewpoints gives a complex and diverse perspective of the impact of agrarian state reform in Maskane.

Although the inhabitants emphasize the significance of technical and agrarian changes within their historical testimonies, they maintain that those changes did not revolutionize all their agricultural practices. Furthermore, the modes of production do not appear to have undergone radical social transformations since the setting up and liquidation of the state farms. Hence social class structures preceding state reforms, such as the hierarchical distribution of agricultural tasks and the types of sharecropping relations are reproduced under slightly different rules. For example, the current notables are not only the descendants of the tribal sheikhs but also the former state farm managers who obtained their positions thanks to education but not necessarily because of their original social statuses. Yet as the paper also suggests, the successive land reforms have enabled the reduction of the social gap between the higher and the lower classes and the subsequent rise of a farming middle class.

Carol Palmer, Lucine Taminian, Waleed Gharaibeh, Council for British Research in the Levant and Jordan University – Agricultural development in Jordan: the case of Ghawr al-Safi

This paper presents preliminary findings of a project exploring agricultural development in Ghawr al-Safi (Jordan) immediately to the south of the Dead Sea, the lowest place on Earth. The project builds on earlier research (by LT) conducted in the 1980s in neighboring Ghawr al-Mazra’. This area benefits from a comparatively good, but limited supply of water for irrigation, fertile soils and an early growing season. Summer conditions, however, are extremely arduous, with malaria formerly endemic in the area.

Safi witnessed a complete transformation in farming practices from grain agriculture and animal husbandry to the intensive cash cropping of vegetables and fruits during the twentieth century, and from local varied to a central authority administering this. Changes in land ownership have been a major part of the process with the local Ghawarneh inhabitants losing some of their best land through the actions of outside agents aware of market opportunities.

In the early 1980s, the Jordan Valley Authority (JVA) implemented a major redistribution of land and established regulations for the control of irrigation and agricultural practices in which the Ghawarneh, most of whom were small land-owners, lost more land due to consolidation into 30 dunum plots, and became either share-croppers or wage labourers. The contemporary cash cropping of vegetables and fruits involves major capital investment in piping, seed and chemicals, benefitting large land-owners and investors. The state authority controls water and limits what is grown. The main markets for the produce are international; however, this is growing increasingly limited due to progressively restrictive produce standards policies in importing countries. All farmers today raise questions concerning even the short-term future of this model of farming.

Rami Zurayk and Farah Samarai, Faculty of Agricultural and Food Sciences, American University of Beirut – Landscape transformations and agrarian change in a village of South Lebanon

Economic globalization has ushered significant agrarian change. Both rural livelihoods and landscape have been seriously transformed. In this paper we present an on-going project aimed at understanding the dynamics of the relationship between landscape and livelihoods by triangulating environmental, socio-economic and cadastral data. We seek to understand how determinants such as agricultural policies, inequality in land distribution and real estate speculations can drive the disintegration of landscapes and induce significant ecological damage. The purpose is to contribute to the knowledge pool available to lobbyist and policy makers. We take as a case study the farm/village of Sinay in South Lebanon. The South, also known as Jaba ‘Amel, has been systematically neglected by the Lebanese state and has born the brunt of the Israeli aggressions and invasions since the mid 20th century. Historically a dryland farming region, except along the narrow coastal strip and the banks of the Litani river, the farming systems of the region have undergone significant transformations. Concurrently, the landscape has also been profoundly altered, as is witnessed by the spread of urban settlements, the proliferation of intensively farmed plastic houses, and the remodeling of the natural geomorphology to accommodate for modern agricultural exploitation. The paper is divided into 4 sections. First we introduce the concept of food regimes and trace their historical evolution, making reference to the concurrent agrarian changes in the Mashreq region. We then briefly introduce the notion of landscape analysis and its potential for studying processes taking place at the nexus of land and people. In the third part, we describe the changes in landscape and livelihoods in Sinay using photographic evidence, hand drawn maps and one-on-one semi-structured interviews. Finally we apply these layers of data to a time series of cadastral maps and draw inferences concerning the mechanisms that have induced environmental and social transformations.

Session 5: Water rights and markets (1) national systems

Roland Riachi, PhD Candidate, CREG, University of Grenoble – Agriculture and food system under the Lebanese hydraulic mission

The presentation takes a historical perspective showing the relation between governance of water and the evolution of the Lebanese food system.

It emphasizes the place of agriculture in the vocational origins of the Lebanese hydraulic mission, embedded in decision-makers’ discourse and large-scale water planning. The status of today’s irrigation infrastructure is examined in relation to the structure of Lebanon's agricultural economy, marked by a polarization between highly fragmented exploitations and large farms. In addition to uneven regional development and neglect of rural areas that undermine the livelihood of small farmers, a rentier supply-chain in Lebanon's primary sector has been consolidated in recent years, which ensures high profit margins to the market's middlemen. Furthermore, a recent trend is shifting agricultural production towards high-value crops, mainly water-intensive fruit intended for export. The Lebanese water footprint and virtual water balance are calculated and examined in order to understand the links between the structures of fresh food procurement, market liberalization, and water infrastructure planning. Finally, the essay will attempt to unlock the debate that froze over a discourse claiming that the Lebanese natural resources endowment limits national food self-sufficiency and increases import dependency.

Karim Eid-Sabbagh, PhD candidate, Department of Development Studies, SOAS, London – Aspects of the political economy of water resource management in Lebanon

The presentation presents preliminary results from my PhD research concerning the political economy of water resource management (WRM) in Lebanon. The focus lies on the role of international development and Lebanese actors – local elites, private interest groups, and the public sector – in the WRM process. The hypothesis of my PhD is that rather than contributing to a restructuring of the state and a shifting of the political economic structures of Lebanon towards more social and ecological justice, the WRM process emerging from the interaction of these actors contributes to a re-entrenchment of existing power structures, these are a neoliberal economy and a sectarian political power sharing system.

This presentation engages academic discussion concerned with water resource management. Over the last two decades, with the growing importance of the climate change debate, the issue of water scarcity has increasingly become a concern of international development actors. This is especially true for the Middle East where all countries are, to a varying degree, already suffering resource shortages. The mainstream literature influenced by neo-Malthusian concerns highlights scarcity. With a limited amount of water available economic sectors are seen as being in competition with each other. Related to this is a growing demonization of agriculture as the main culprit, using up the lion's-share of water resources. Integrated water resource management (IWRM) infused with neoliberal ideology is advocated as a set of tools to manage and balance competing uses of water.

This presentation focuses on the water resource management process during last two decades of reconstruction and development in Lebanon after the civil war. Two issues stand at the forefront of this, geographically uneven development and related imbalances in the development of different economic sectors. The post civil war reconstruction efforts centred heavily on Beirut at the expense of the peripheral regions and with that had a strong bias against agriculture. From the onset the focus was on the creation of a real-estate speculation economy that favours services and banks, such as financial and consumption oriented sectors over the productive sectors agriculture and industry. Beyond the ideological choice embodied in the privileging the real estate and financial sectors and the (intentional) neglect of the agricultural sector, this act represents a fundamental WRM decision which is also responsible for the abysmal water management in agriculture. Within its ideological constraints, mainstream IWRM (as fluffy a concept as it might be) is thus seen as too narrowly defined to address these structural imbalances and their material outcomes and might actually work to exacerbate them.

This will be explored via a juxtaposition of the agricultural sector with the real-estate sector and the government strategies towards each. This structuring of the Lebanese economy will be related to water management issues and the material effects on the population and agricultural produce as well as on resources and the environment. Furthermore, government expenditure in infrastructure and policy efforts – all elaborated with the heavy involvement of international development actors - will be analysed in order to understand the allocation of the resources water and capital. The WRM process of the last twenty years is seen as centred almost exclusively on infrastructure. It is suggested that the allocation of resources is articulated between the political and economic interest of local/national elites and international actors and generally in favour of the capital-rich within and across economic sectors and this to the detriment of long term development prospects.

Session 6: Water rights and markets (2) irrigation systems

Sharafaddin Saleh, Irrigation Engineer, Water and Environment Center, University of Sanaa – Economic and social impact of technical improvements and renewal of spate irrigation systems in Yemeni wadis

التأثيرات الاقتصادية والاجتماعية لتحسينات الفنية في منشآءت منظومات الري بمياه السيول في الوديان اليمنية

اليمن تعتبر اول دولة في العالم في ممارسة الري بمياه السـيول، وقد شهدة انظمة الري بمياه السيول قوة في عهد السبئيين في الافية الاولي قبل الميلاد حيث تم تشييد سد مأرب العظيم الذي انهار قبل 2400سنة. تعتبر الاراضي المروية بمياه السيول من اهم الاراضي الزراعية في اليمن، حيث تعتبر من اخصب الاراضي الزراعية واكبر المناطق لإنتاج الحبوب والفواكة، وتبلغ مساحتها الكلية 120000هكتار (اى تمثل 24% من مساحة الاراضي المروية و 11% من المساحة الكلية للأرض المزروعة في اليمن)، والمساحة التي تغطيها المنظومات الحديثة للري بمياه السيول 90000هكتار.

ومنذ خمسينيات القرن الماضي و حتى الوقت الحاضر، قامت الدولة وبدعم من المانحين بتوظيف استثمارات

كبيرة في مشاریع إنشاء منظومات حدیثة للري بالسيول (الحواجز التحویلية و شبكات قنوات توزیع مياه الري) في اربعة ودیان رئيسية من أودیة تهامة، وهي: وادي زبيد، وادي مور، وادي رمع، وادي سهام وغيرها من الوديان الاخرى المنتشرة في عدة مناطق في اليمن.

وهذه السياسات التي تتبعها الدولة في تحسين وتحديث منظومات الري بمياه السيول في وديان تهامة بهدفة توسيع الارض الزراعية وزيادة الانتاج الزراعية والحيواني لمواجهة الاحتيجات المتزايدة لتوفير الغذا للسكان ودعم الاقتصاد ا لوطني ومحاولة تخفيف الفقر في مناطق الري بمياه السيول.

سيناول هذا البحث دراسة التاثيرات الاقتصادية والاجتماعية لتطوير وتحديث منظومات الري بمياه السيول من حيث زيادة الانتاج الزراعي والحيواني وتوسيع المناطق الرزاعية وتوفير الغذا لسكان اليمن بشكل عام وسكان مناطق هذه المنظومات بشكل خاص ، وكذلك تأثيرات التحسينات والتحديث لهذه المنظومات في استقرار سكان المنطقة وتحسين حالتهم المعيشية والتخفيف من الفقر والحد من هجرة السكان الى الدول المجاورة.

Ahmad Al-Bakri, Agricultural Engineer, Water and Environment Center, University of Sanaa – Water rights and maintenance and operation of spate-irrigation channels

The paper begins with an overview of ghayl (water from springs with a year-round flow) and sayl (spate flood water) irrigation systems, noting that the Yemeni government has completed neglected the first in terms of its protection or management or maintenance. The paper goes on to note the comparative neglect of development of sayl irrigation systems and, in cases where the government introduced new diversion structures, the neglect of traditional systems of management and rights to water. Four different systems are considered: on the Red Sea versant Wadis Maur and Siham in the Tihama, and in the Southern Indian Ocean versant Wadi `Adam (Damir b. Muslim) and Wadi Du`an.

Session 7: Investment of oil rent: the landscapes of pastoralists and farmers

Dawn Chatty, Professor of Anthropology, Refugee Studies Centre, Oxford University – Dislocated, displaced and dispossessed in the shadow of the Arab oil economy: pastoralists, conservation and oil in the Central Desert of Oman

Agro-pastoral and pastoral communities in the Arab Middle East have been spectacularly affected by both conservation schemes and oil extraction efforts. Traditional subsistence and mobile livelihoods in these extensive areas of arid and semi-arid lands have gradually been undermined, first by government and international donor efforts to ‘develop’ pastoralists by turning them into ranchers or farmers and second by oil company determined to regard traditional grazing lands as terra nullius and thus not accountable to those seeking socially responsible involvement with stakeholders in oil extraction regions. Current views of the desert and its fringe as empty of permanent settlement has resulted in a denial of authenticity of the very populations which have lived on these lands for centuries. Using as a case study the pastoralists of the Central desert of Oman, this paper sets out to describe and analyse the process of dislocation, displacement and threatened dispossession of pastoral groups whose territory overlaps with conservation and oil extraction industries.

Amat al-Ghafour `Aqabat, Sociology Department, University of Sanaa – Economic activities and hardships among nomadic populations of the Yemeni hinterlands on the Saudi border

The presentation examines the economic and social hardships faced by communities living in part from pastoral production. It discussed the long-term effect of different government policies of the North (former YAR) and South (former PDRY) with regard to the nomadic populations. It calls for greater government investment and engagement with the needs of this sector of the Yemeni population.

Myriam Ababsa, Associate Researcher, IFPO, Amman – The contemporary market in land south of the city of Amman

This paper presented preliminary work on the agrarian transformation south of Amman in the context of urban sprawl and high speculation in land. Since the opening of the airport road in 1978, farming practices changed totally from rain fed wheat and barley agriculture t