Property Rights and Land in Lebanon and Tunisia

Two Articles from JSSJ Journal No. 7 "The Right to the Village"

The following two articles are from the Issue No. 7 of Justice Spatial | Spatial Justice (JSSJ Journal). Follow the links for the full articles.

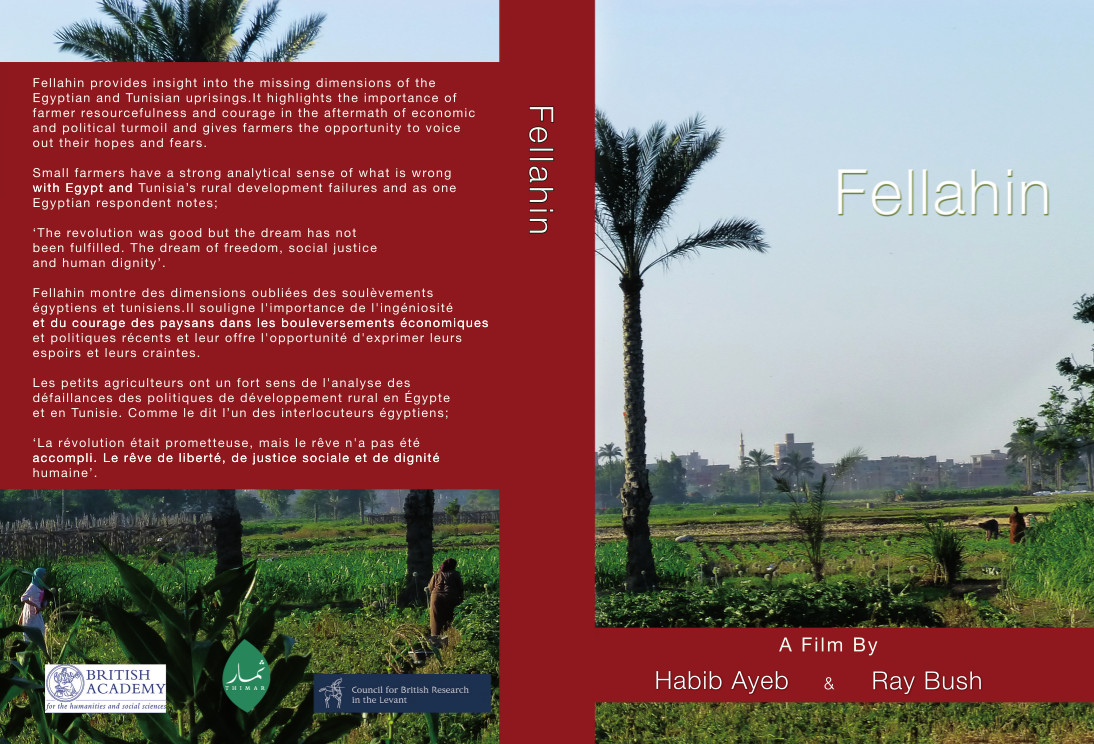

Land injustices, contestations and community protest in the rural areas of Sidi Bouzid (Tunisia): the roots of the “revolution”?

Injustices foncières, contestations et mobilisations collectives dans les espaces ruraux de Sidi Bouzid (Tunisie) : aux racines de la « révolution » ?

Several studies have sought to explore and analyse the links between what is called the “revolution” in Tunisia and (r)evolutions in rural areas, marked by major transformation in agrarian structures, production techniques and social organisation (Elloumi 2013, Saïdi 2013). Some explore the ways in which the sociopolitical movements were organised or the links with food issues (Gana 2011 et 2012), others study the process of peasantry marginalisation at different scales (Ayeb, 2013). Though less researched, the question of land in rural areas is nevertheless an issue of spatial justice and injustice, and one may wonder whether it underlies the protest movements against the regime in Tunisia. This article seeks to show the links between inequalities in land rights and the protests that led to the toppling of the government in January 2011.

Plusieurs travaux s'attachent à explorer et analyser les liens entre ce qui est appelé la « révolution » en Tunisie et les (r)évolutions dans les espaces ruraux, marqués par une importante transformation des structures agraires, des techniques de production et de l’organisation sociale (Elloumi 2013, Saïdi 2013). Certains analysent les formes d'organisation des mobilisations socio-politiques ou les liens avec les questions alimentaires (Gana 2011 et 2012), d'autres étudient le processus de marginalisation des paysanneries aux différentes échelles (Ayeb, 2013). Moins étudiée, la question foncière en milieu rural figure pourtant parmi les enjeux de justice et d'injustices spatiales, et on peut faire l’hypothèse qu’elle est sous-jacente aux mouvements de contestation du régime en Tunisie. Cet article cherche à montrer les liens qui existent entre les inégalités des droits sur la terre et les mobilisations qui ont mené au renversement du pouvoir central en janvier 2011.

‘The right to the village? Concept and history in a village of South Lebanon’

Le droit au village? Concept et histoire dans un village du Sud-Liban

In the village of South Lebanon where we have been working on documenting the long-term relation between land-tenure and land-use, villagers speak proudly of how they claimed their ‘rights’ from landlords. In the case of both house plots and the cultivation of land, they express this in terms of haqq, the equivalent of ‘right’ in the particular and of justice in the abstract. On occasion they speak of such action in the abstract, mutalabat bi-ʾl- haqq, demanding rights/justice through struggle and social movement. In practice, their contestations achieved some of their ends but not all. And so, in line with the theme of this issue, we thought to ask whether their claims to rights could be fruitfully conceived as expressing something broader: a kind of ‘Right to the Village’, in the spirit of Lefebvre’s much-feted slogan, the ‘Right to the City’- although the villagers did not interpret their actions through any such global abstraction.

Dans notre village d’étude au Sud-Liban, nous travaillons sur la relation entre la propriété de la terre et son exploitation sur une longue durée. Les villageois parlent fièrement de la façon dont ils ont réclamé des « droits » à leurs propriétaires. Qu’il s’agisse de terrains à bâtir ou d’exploitation de la terre, ils l’expriment par le terme de haqq, équivalent de droits au sens particulier et de justice au sens abstrait. Parfois, ils évoquent une telle action dans l’abstrait, mutalabat bi-ʾl- haqq, et demandent des droits/la justice à travers la lutte et le mouvement social. En pratique, leurs contestations leur permettent d’atteindre certains de leurs objectifs, mais pas tous. Aussi, en lien avec la thématique de ce numéro, nous nous sommes demandé dans quelle mesure leurs revendications pouvaient de manière pertinente être conçues comme exprimant quelque chose de plus large : une sorte de « droit au village » dans l’esprit du slogan de Lefebvre si célébré - « le droit à la ville » -, alors même que les villageois n’interprètent pas leurs actions sous une telle abstraction globale.