Restructuring Food Production Development Project, Open-market Economy and Agrarian Value Relations

The Case of Ghor al-Mazra`s in Southern Jordan Valley

This report is based on six months intensive research, including participant observation, interviewing farmers (small, large, and investors), health service providers; in addition to reviewing recent literature on development, Jordan’s economic policy and development reports, and the records of the Jordan Valley Authority.

Jordan Valley Development Project

The Southern Jordan Valley benefits from a comparatively good, but limited, supply of water for irrigation, fertile soils and an early growing season of vegetables. It is estimated that over 60% of the value of national agricultural production is grown in the Valley. Since the inclusion of Jordan in the world market economy during the 20th century, the valley witnessed major transformation in farming practices from cereals production and animal husbandry to capitalized production of vegetables and fruits which became the only form of production with the implementation of the Jordan Valley Project in the mid-1980s. The shift to capitalized production led to changes in landownership whereby the local Ghawarneh farmers lost their land to capitalist farmers as well as to changes in forms of land use and of labor.

In the early 1980s, the Southern Jordan Valley, which extends from the south of the Dead Sea to the north of Ghor al-Safi, was included in the Jordan Valley Project. The Jordan Valley Authority, a ministerial body, was entrusted with the integrated socio-economic development of the Valley, land allocation, and the operation and maintenance of underground pipeline networks that link each farm to the water resource; farmers were responsible for the setting up and maintenance of the drip irrigation system on their farms.

According to JV Development Law No. 19 of 1988, landownership was confined to the JVA and farmers were entitled to usufructuary rights to land. This meant that farmers did not have the right to sell their land, but their children were entitled to inherit it, in which case they would be considered partners in the holding. The area of 14,670 dunums included in the project was divided into 30-40 dunum units which were redistributed according to the following rule: Minimum land holding was stipulated at 30 dunum units and the maximum at120 dunums. Permission was granted for units to be shared between two, three or four farmers, thus the minimum effective farming unit was 7.5 dunums.

The land distribution changed the structure of land ownership. The large landowners whose holdings exceeded 120 dunums, managed to register extra land above the maximum in the various names of their family members. On the other hand, the small land owners who owned less than 7.5 dunums (all of whom were Ghawarneh) and made up 60% of all owners at that time, were given the option to pay for the extra dunums needed in order to be entitled to land ownership. Many did not have the cash to pay and lost their land. More importantly, the committee assigned to identify the entitled farmers was composed of absentee landlords and state officials who had never set a foot in Ghor. Large landholdings were allocated to relatives of committee members, to absentee landlords and influential state officials.

The project also reshaped relations of production in the valley. Subsistence farming was destroyed, as small farmers, as mentioned above, lost their small family farms, which constituted the material basis of their subsistence work and the main source of food security for their families, thus becoming wage labourers selling their labour to big land owners. Moreover farmers lost control over water resources, the second most important means of production in the Jordan Valley; and the irrigation system they had developed and administered (a co-operative activity) for the last seven decades was replaced by a pressurized irrigation system administered by JVA.

Open-Market Economy

The state economic policies over the last four decades enhanced capitalist relations of production. The Economic Reform Program of the late 1980s aimed at the liberalization of economy and the elimination of all barriers to the movement of investment, labour and capital, thus enhanced capitalist relations of production and the commercialization of agriculture. Following the membership of Jordan in the WTO on April 2000, tariffs on agricultural products imported into the country decreased between the years 2008 and 2015 to 8%; the total subsidies for farmers were reduced by 13% over the seven years; and the rate for agricultural export subsidies were reduced to 0%.

Accordingly, the JV development law 19/1988 was amended (no. 30/2001) to allow for larger farming units (Article 22.b.) and for private sector participation in management contracts, and in water utilities. Land tenure laws were changed to allow for private ownership of farming land. Unless the land is mortgaged, a farmer can now obtain an ownership deed from the land department. Many small farmers are concerned that they will lose their farms for failure to pay the mortgage. JVA records show that large tracts of land have been taken over by agribusinesses and devoted to export crops.

The future of Agriculture and the restructuring of local economy

The words farmers, small and big, often use when talking about the future of farming in Mazra`a are “disastrous” and “catastrophic.” The destruction of the local practical knowledge (such as seeds and techniques of a sophisticated irrigation system) deepened farmers’ vulnerability to the merchants of the central market in Amman who monopolize the marketing/provision of agricultural inputs. They sell these commodities at high prices and buy farmers’ products at low price. Small farmers usually buy the inputs on credit on the condition that they sell their product to the merchants who in turn decide the price farmers are paid. The closure of the borders with Syria and Iraq, the major importers of Jordanian agricultural goods, created a surplus of agricultural products, thus strengthening the merchants’ grip on small farmers. Farmers often sell at a loss which made them feel, as one farmer put it that they “… work for the merchants in Amman”; others may choose not to pick their product or to throw it on the road to Amman as a sign of protest. The majority are in debt and live in hiding to avoid imprisonment.

Liberal economists and national and international NGO’s prescribe “income generating projects,” as the “magic remedy” to poverty and unemployment. Microfinance associations that provide loans to “low-income beneficiaries” to “empower them economically,” have mushroomed in Ghor al-Mazra`a since early 1990s. Most of the associations target women who quite often get the loan to support a husband to get a car or a son to get married. According to newspaper reports Micro Funds for Women make high profits though they claim that they are non-profit organizations. Many female “beneficiaries” in Ghor al-Mazra`a who failed to pay the large interest rate live in hiding to avoid imprisonment for failing to pay back the loans.

The most recent project for restructuring the local economy is developing the “culture economy” of al-Mazra`a by promoting it as a rural touristic site. Mazra`a is currently witnessing an unprecedented proliferation of initiatives by NGO’s in which local cultural resources are seen as the key to improving the social and economic well-being of its inhabitants. An exchange-tourism program organises trips to al-Mazra’a where local women teach the visitors supposedly the traditional crafts and serve them traditional food in return for a sum of money paid to the local community. The commodification of al-Mazra`a involves re-inventing its culture and the everyday life of its women. The making of “supposedly” traditional bread and dishes is turned into a theatrical scene that ignores all signs of the hard labour of baking the bread, keeping the crawling babies away from the fire, or chasing off a goat trying to get a bite or two.

Nutrition and Health

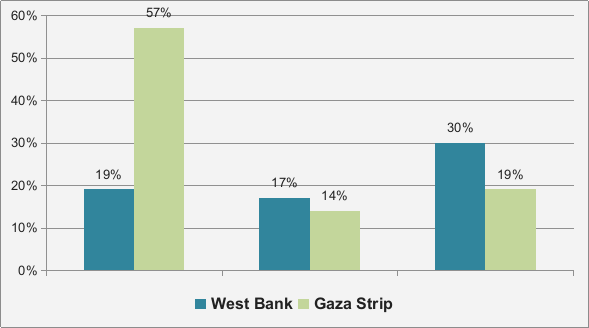

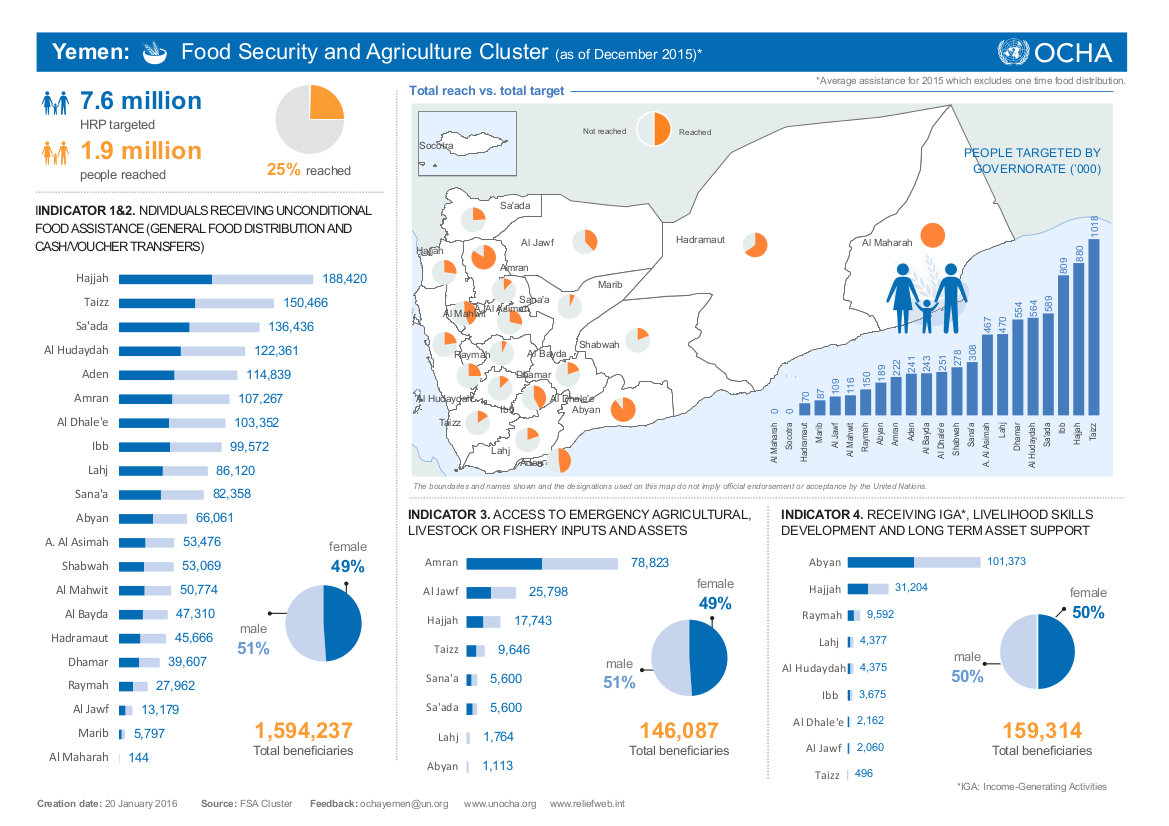

Unemployment and poverty are widespread in the Southern Jordan Valley. According to the recent studies on poverty in Jordan, more than 33% of the population are below poverty level and more than one-third of youths are unemployed – a fact that has a serious negative impact on their nutrition and health. With the destruction of family farms, families lost their source of food security. The municipality laws whereby the raising of animals (chicken, goats, cows, etc.) in the back yard are not allowed, and the scarcity of water for home use put an end to house gardens. Families used to produce their food all through the year, and when/if they ran short of any food item such as tomatoes, onions, beans, eggs or milk they used to get it from neighbours. The resentment of a landless sharecropper who used to farm 30 dunums is very telling:

I am sick and old, I can’t farm. We don’t eat fresh vegetables any more. When you pass by a farm, female labourers turn their faces to the other side pretending they haven’t seen you. They don’t give as they used to do in the past, everyone is in need and they want to feed their family first.

As the culture of food exchange is dying out, consuming fast or frozen food has become a sign of, to use the words of the ex-mayor of Mazra`a, “tamaddun wa-taqaddum”, i.e. “urbanity and progress.” The shelves of small shops and “super-markets” on the main road are packed with canned meats, frozen foodstuffs and soft drinks some of which have passed expiry dates. Snacks and sweets made by women funded by international NGO’s are sold in school canteens.

According to doctors and health service providers at the Public Health Centre that serves more than 200 patients daily, the most common health problems they deal with are high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, and anaemia, all of which are due to malnutrition. The midwife who follows up pregnant women through pregnancy reported that obesity and high blood pressure are common among women of age 35+ years whereas diabetes starts at an earlier age. The records show that 30-40% of female patients suffer from anaemia, and that anaemia, food poison and obesity are also common among students who depend on snacks, sweets and soft drinks as their main food. Heart attack is very high among young men; a fact that was confirmed by the physicians but they did not have the statistics as not all deaths are registered in their records.

Right to Land

With the implementation of the JV Project, the Ghawarneh felt that their land had been “plundered and been pulled away from underneath their feet.” They organized a series of protests, reclaiming their right to the land they had been cultivating for hundreds of years and asking for the cancellation of land distribution. In 1989 they attacked the JVA offices and burnt their vehicles and records. Their representatives met with high officials who promised to help, but their demands were shelved and their case was closed.

In 2011, the Ghawarneh in Mazra`a and Safi had a general meeting, and wrote and open letter of 46 pages addressed to the king highlighting the injustice done to them by the “JVA committee” in charge of land redistribution and listing names of “high state officials”, who never set a foot in the Ghor yet were allocated several units and the names of committee members who allocated units to their families. It’s a powerful letter, and an historical document that tells the history of landownership in JV starting in the early 1920s up to present. As expected the letter was ignored.

Recently, a group of young “black men” from all over Jordan mobilized to establish a party they called hizib al-jibah al-sumur, The Party of Brown Foreheads.” (Forehead in Arabic symbolizes dignity, honor, and bravery). Their application to get a license from the Ministry of Political and Parliamentary Affairs to set up the party was turned down on the bases that Jordanian law does allow the formation of party based on race, ethnicity or sect. The organizing committee changed the name of the party to the Jordanian Civil Society Party and reapplied but again the application was refused.