Seminar: Agriculture in the shadow of the Arab oil economy

London, LSE, June 24-25th 2011

This project held a first workshop on June 24-25th 2011 to develop a network of anthropologists, economists and agronomists concerned with the problems faced by the agrarian sector, source of food and workers for the Arab economy. The region that was the cradle of agriculture exhibits today the greatest food insecurity in the world. Its stark dependence on imported food is not infrequently treated as a technical problem arising from natural aridity exacerbated by climate change, from population growth, or, less commonly, from macro-economic policy. All are critical factors. Yet research that tackles change in the region’s rural areas in an integrative manner remains extremely rare. At the macro-economic level, one needs to ask how the region’s food insecurity relates to its equally record-breaking levels of unemployment, income inequality, and international armed conflict. At the micro social-economic level, one needs to explore how the development of larger-scale capitalized agriculture relates to the survival (or demise) of small-farming and the work of men and women. It is our aim to bring together sociological, agronomic and economic expertise, to develop research on the ground to understand the causes that thwart the productive potential of rural farming and pastoral societies, and on that basis to propose interventions and changes to policy to release that potential.

(Our geographical compass concerns the Arab East including Egypt and, potentially, Sudan.)

Below is a brief report on the June 2011 workshop. A second larger workshop is planned for early January 2012 in Amman where we look forward to being joined by more colleagues from the region than possible in London. We are grateful to the Centre for Middle Eastern Studies and Department of Anthropology at LSE, and above all to the British Academy for support of these workshops.

Structure of the June 2011 workshop

Prior to the workshop

Participants in the workshop had been invited to speak to the present structure of rural labour and food production from their own perspective and to characterize the state of research. Prior to the workshop particular themes were identified which participants were invited to address:

(a) Macro-economic policy and the crisis of agricultural systems: to what extent are national and international macro-economic policies rendering whole sectors of agriculture unviable?

(b) The relation between Arab migration to the Gulf oil economies and the wider patterns of Asian migration: are there commonalities in the experience of Arab rural migrants, those of today or of an earlier generation, and contemporary Asian migrants to the core oil-producing Gulf states?

(c) Analysis of the rural production sector as an integrated whole where crop and animal production is combined with other productive work on and off ‘farm’, notably how pastoral and agricultural production are articulated today?

(d) The relation between male rural out-migration and the changing nature of production and of women’s work in the rural areas.

Results and development of research questions

The thrust of discussion was both to press for more integrative frameworks of analysis and to engage with those on the ground who were seeking to respond to the crises of the agrarian sector of Arab economies.

The agronomists argued that analysis of land-use or the more aesthetic term ‘landscape’ permitted a conceptual integration of physical forms (settlement, types of cultivation, irrigation, technology on land, animals and their human minders) and living processes of land-holding (the common, the state and the private), production, and work. Critical historical documentation of ‘landscape’ can reveal the blockages to access for pastoral production as well as log the transformation of forms of livelihood and production. They thus argued for foregrounding the documentation of ‘landscape’ as a heuristic tool.

The development economists argued for the need to document in rather classical terms the parameters of agrarian transformation over the last decades: the legal and administrative frameworks of land ownership and tenancy rights, the legal status of (gendered) agricultural labour, and the differentiation of the agrarian sector according to scale, labour-relations, capitalization and markets. They felt that the strength for the network of combining anthropological field research – which attempts to understand and document the lived experience of people – with macro-economic perspectives and agronomic analysis was to challenge misleading, abstract social science legitimation for policies that time and again have borne results very different from those announced.

It was agreed that it was important to foreground ‘food sovereignty’, i.e. control over and prioritization of producing basic foodstuffs, as against the notion of ‘food security’. The first opened the perspective of active participation in production at local and regional levels, whereas the second tended to treat the ‘food deficit’ as a quantitative problem of international exchange or distribution. A parallel distinction was made between considering cultures of food consumption as linked to local and regional production – that is diet and cuisine as fundamental cultural and economic characteristics – as opposed to a vision of food merely as quantities of global food stuffs available to the world’s mouths and markets. This entailed a certain management of the market in the interest of ‘food sovereignty’.

The question was raised as to whether at present there was a regional framework of analysis beyond the specialised work of international and Arab organisations and whether, however modest our fledgling research network remained, we could contribute to the elaboration of such a regional analysis. By holding a second workshop in the region, with a more focused theme – the relation of smaller, often domestically organized, farming and herding to the larger-scale often more capitalized agricultural enterprises – we will further explore the possibilities of developing of a regional interdisciplinary research problematic.

The wider framework: international migration and global economic regime (24th June)

Session 1: Labour and the agricultural sector

Andrew Gardner, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, Department of Comparative Sociology, University of Puget Sound, USA – Overview of labour migration to/within the region

Gardner had worked on Asian male migration to the Gulf (Bahrain and Qatar), see his City of Strangers: Gulf migration and the Indian community in Bahrain (2010). From this work he raised questions of a comparative nature about the integration of labour from agricultural areas globally into employment in the oil-producing states of the Peninsula, the parallelisms and differences with Arab migration, and the division of work in Gulf. Too often Asian and Arab labour migration are viewed separately and so he sought to raise questions about that relationship in his talk.

Whereas ‘citizens’ of the oil-producing states worked primarily in government jobs, migrant labour estimated at some 15-20 million persons in the Gulf States entered employment under the sponsorship system entailing the personalization of government of labour. Yet migration is an industry in itself governed by manpower agencies in the Gulf and labour brokers in S Asia in which mis- or dis-information is integral to the profitability of the system. Gardner’s work revealed that migrants had to pay on average $2,000 to secure work in the Gulf. Thus, one question concerned the profitability of labour importing itself, notably whether Arab rural migrants had to advance similar sums to secure work or in fact passed through different kinds of channels en route to work in the Gulf. (The paper by Alajmi, see below, addresses one case study that in part responds to these questions.)

The other comparative set of questions concerned the impact on the largely rural sending areas. It goes without saying the poorest of the poor do not have the means to access such migrant work and that the experience of working in the Gulf heightened the valuation of consumerism, all the more for migrants who were prevented by the security guards from entering the shopping malls in the cities where they laboured. At the sending end, the decision (and raising of money) to send a male migrant was a collective household one, not simply that of an individual, thus reinforcing ‘extended’ versus ‘nuclear’ family relations. And in that process both women and the elderly made particular sacrifices in terms of cash and labour at home. Gardner stressed the manner that not only the particular households but the sending countries more generally were abjected in the process of migrant labour exportation to the oil-economies. He asked whether similar processes were at work at the sub-regional level with regard to Arab migration or whether the political factors were so central there that decisions to import or to exclude Arab labour exhibited quite different patterns.

Ali Kadri, Visiting Senior Fellow, Department of International Development, LSE – A post-revolutionary strategy for employment in the Arab Mashreq

Kadri responded by attempting to characterize the place of labour in the Arab oil-economy more generally. The starting observation was how through the circulation of oil-rent between the oil-producing and the other Arab states, a regional economy had been created wherein consumption was funded by oil-rents not by value-adding labour. As a result, not only in the labour-receiving countries but also increasingly also in the labour- sending countries, a regional rent model is today dominant. Where there had been relatively more autarchic systems of production, these have over the years been integrated into the whole. Kadri noted that the official statistics scarcely indicate the magnitude of the problem: if we take as a definition of employment a person who works at least 20 hours/week and covers his/her basic needs, then we would find rates of unemployment at about 50% of the work-age population, not the 20% generally cited. Indeed on average in the region some 25% of the work-force is employed by the public sector, some 50% unemployed, leaving only 25% in private-sector full-time work. Not surprisingly, wages have fallen, thus in Egypt they are about half what they were eight years ago. Likewise, the basis of knowledge-production is very extremely small (and education of elites geared to the export of high-quality labour abroad), and oil-rent also allows the importation of labour-saving technology.

Conventional economists (and international organisations) continue to explain the high (official) rates of unemployment in terms of a rigid labour market and call for further labour-market deregulation. In fact the labour supply is extremely elastic and the solution proposed is absolutely incapable of addressing the problem. Labour is among the least legally protected in the world; it is very difficult to speak of the meaningful existence of labour law; for example, Kuwaiti labour law contains no definition of a wage or a salary. One faces regional economies with extremely reduced productive capacity and yet with no balance of payments constraint, i.e. with ample capital. Any solution to this disastrous economic structure would require major action by the state, but this clearly is not possible without radical change in the character of the regimes and the economic orthodoxy to which they subscribe. Such states have to take food production as seriously as work, knowledge and production in other sectors; they would also need to develop strategies to grasp control over the privatization of flows of oil revenue regionally and internationally. In this sense, the problems of the agricultural sector are but symptoms of wider economic problems.

In Kadri’s words: For the regional unemployment rate to stay in the double digit category for more than a decade and then to respond poorly to the recent fervour of economic growth rates implies that there is something fundamentally flawed with the policies in place. If it was about the International Financial Institutions (IFIs) ‘macro fundamentals,’ then, in the present oil boom and up to the point at which the Arab revolutions were sparked, these were well positioned: the fiscal accounts were in surplus, the inflation rates were under control and the reserves were way up high when capital and trade accounts were wide open. Despite that, the unemployment rates and income distribution measures remained ill-placed globally. In the preponderance of rents, the remaining productive economy and its capacity for employment generation cannot keep pace with the rate of growth of the labour force nor fully absorb initial levels of that labour force. Therefore, unemployment is broadly cyclical. In fact, public sector employment and declining productivity growth have been, to a large extent, a blessing in disguise, acting as a social safety-valve in the absence of unemployment insurance programs. The welfare implication of this labour market condition indicates that the trickledown effect is obviously missing; more importantly, the labour share stayed excessively low - the lowest globally. And for matters to take an alternative course, one must make the policy of employment creation central to economic policies with rent redistribution creating more employment in the short term and give preferential status to regional capital and labour in the intermediate to long term. Pursuant to the recent revolutions, employment policies are best set in a regional cooperation framework and with a social efficiency criterion for employment, under which, socially valued and relevant work reimburses the costs incurred at present from the long term gains it generates. Equity, in an Arab context, must come before the neo-classical notion of efficiency. Development, it has to be remembered, is a long term process and not a quarterly reporting exercise on financial performance.

Session 2: Transformation of food production systems

Rami Zurayk, Professor of Agricultural and Food Science, Faculty of Agriculture, American University of Beirut - Evolution of food systems, landscapes and livelihoods

Zurayk problematizes the usages of ‘food security’ within international and national policy-making agendas and development programmes. While food security policies may articulate that the right to nutritious food must encompass ‘access,’ ‘availability’ and ‘use,’ they remain embedded within market enterprises. Therefore much like Kadri’s critique of economic models of liberalisation and privatisation, Zurayk questions the efficiency of food production and sustainability within such paradigms. While trade liberalisation may have created some ‘pockets’ that are food secure within the Arab world, there is, by far, a larger problem of poverty, famine and malnutrition. At one level, the (extreme) disparities between zones that are food secure and insecure in the region can be illustrative of the spatialisation of capital. Situated within a global perspective, they are also indicative of the ways in which food-security projects foster food-dependency. Reliance-and this is increasingly so-upon imported food and agricultural stuffs has political, economic and social ramifications; and thus adds another dimension to the perspective of labour exploitation discussed earlier by Gardner and Kadri.

The ‘driving force’ of food dependency has to do with large landowning urban elites who deploy rent-seeking strategies in order to maintain their monopoly privileges within rural areas. Alliances made with development agencies, also entrenched within a market orientated framework, only exacerbate labour inequality and food unsustainability. Zurayk offers the example of a UNDP led research report entitled The Development Challenges in the Arab Worlds (DATE). The report shows that the self-sufficiency ratio of cereal had increased to 60% across the region. This is similar for dairy production that went up to 70% and meat increasing to 80%. Drawing on his own research, Zurayk presents the case that these figures are extremely problematic and presents a distorted image of the actual modes and forces of production occurring across the region. Lebanon is a case in point, where the United States is its biggest agricultural trader. Through its acolyte, USAID, the United States mainly exports corn which is sold as feed to the local industrial chicken farms. Yet in spite of the high number of chicken farms located across the country, it is cereal and not meat which is more commonly consumed within local communities. Such views and practices fail to understand and use the full potentiality of the land from both socio-cultural and agronomic perspectives.

Instead Zurayk argues for a more perceptive understanding of land in terms of the physical attributes of the land. This is to move from a one-dimensional system into a multi-dimensional one. In other words market-driven agro-industries, characterised through mono-culture, perpetuate the cycle of zones of food security alongside insecure ones as well as forms of food dependency. Here the concept of ‘landscape’ as applied by Zurayk is a methodological one that is used to map out a cultural history of agrarian practices within a region. Through such a lens, transformations of land into an agriculturally diverse landscape can take place and be more suited to local methods of production and consumption, subsequently giving way to incentives more in line with principles of food sovereignty.

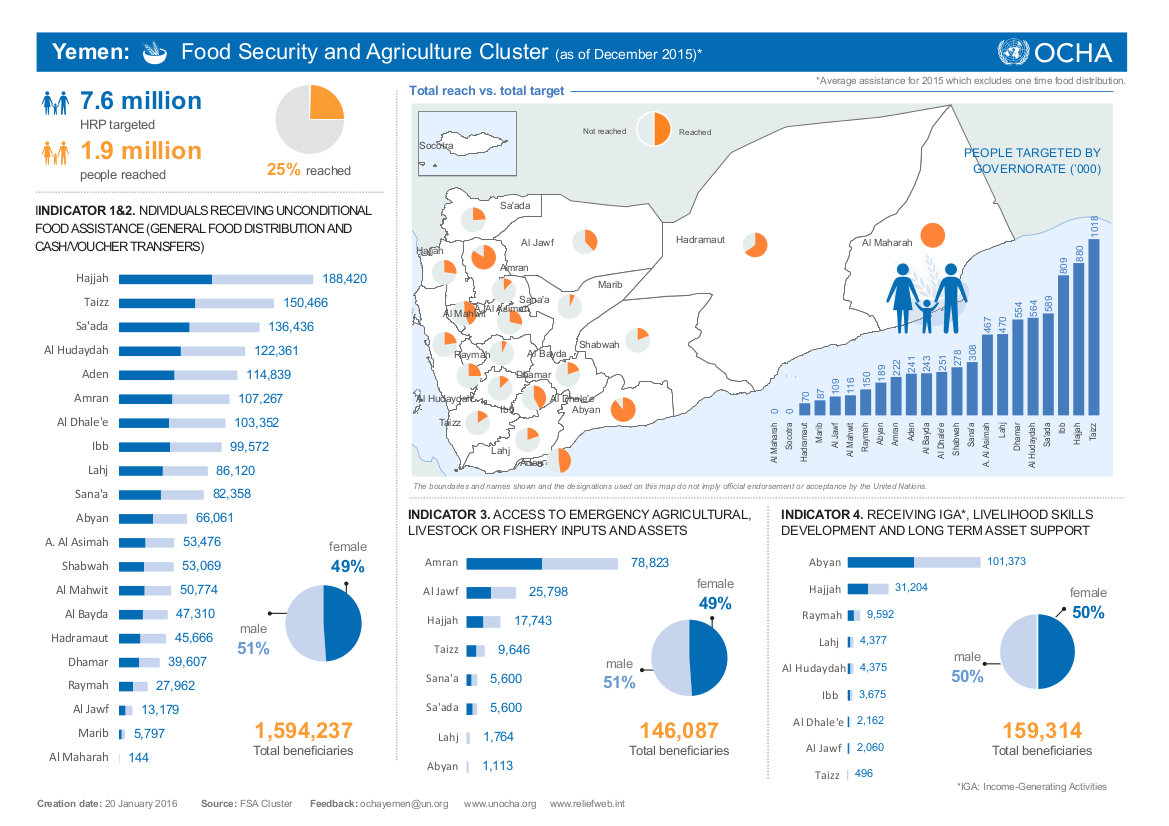

Frédéric Pelat, Agronomist, ONG Iddeales, Sana, Yemen - Food Systems and Natural Resources Linkages facing Socioeconomics Mutations in Yemen

Pelat explains that currently 93% of the water is used - and wasted - in agricultural production. This proportion is increasing despite rising domestic needs due to high population growth and this has direct consequences upon food production in country, all the more given that water, like cultivable land, is a scarce resource in Yemen. A shift in agricultural production across Yemen took place during the 1970s and 1980s. Until that point, 82% of the agricultural surface area was rain-fed and water management occurred through terrace farming. There was a cultivation of cereals such as sorghum, barley and wheat as well as legumes. With the introduction of fruits, vegetables and also the expansion of qat as cash crops in some regions, the terrain of the rain-fed zones has dramatically altered. Land erosion is occurring at a rate of at least 20%-and this is predominantly across the terraces. In line with Zurayk, Pelat argues that mono-cropping and market-dependence - both of which are interrelated - have had direct impacts upon water scarcity, poor diets and malnutrition. As Pelat points out, farmers when purchasing food from the market will aim at compensating deficient production in grains, mainly wheat, and not at diversifying their food basket with fresh vegetables or fruits, given both their limited income and the absence of such crops in the traditional cropping pattern.

Two case studies are provided in the presentation in order to shed light upon the problems faced when addressing issues of market dependency in rural areas. The two villages, originally both reliant on rain-fed farming, are located within a few kilometres of the other, but each practices a different agricultural system today. One uses techniques for sustainable agriculture and adheres to more traditional practices, notably with regard to the production of seeds and agro-biodiversity. The other engages with more intensive methods of irrigated farming and produces crops to be transported to urban markets. Pelat notes that in spite of the diversity in agriculture in the first village, local farmers still had to buy a substantial amount of wheat from outside sources due to insufficient production. As non- local wheat varietals (like “Kanada”) have displaced local cereal varieties, notably sorghum and barley, there has been a shift in dietary habits as well. As Pelat explains, in the second much wealthier village, although there has been much work to intensify cultivation practices and water systems since the 1970s, farmers are still buying foreign wheat from local markets due to the market orientation of their own production, now mainly based on potatoes and vegetables. Intensified agriculture and market access have failed to solve food insecurity and to balance food diversity; and, today, one of the many problems faced are health problems linked to water pollution from chemicals used in intensive farming.

Session 3: Employment and food insecurity

Abdullah Alajmi, Course Chair, Social Sciences, Arab Open University, Kuwait - Food insecurity and Yemeni employment in the Gulf: A case from Kuwait

Alajami examines the employment conditions of migrant workers who come from the rural regions of Hadramawt in Yemen to work in Kuwait. Migration from Hadramawt to Kuwait began in the 1940s with the advent of the oil boom. Up until the first Gulf War in 1991, there were at least 100,000 Yemenis working in Kuwait. Many specialised in domestic house services working for well-established Kuwait families; and it is their experiences of domesticity which shape their relationship with Kuwaitis today. Currently there are about 20,000 labourers who work as shop assistants, government sector employees and some also hold menial roles in Kuwaiti owned companies. Yet they have inherited these roles (not jobs) from their forefathers, as their Kuwait sponsor is a kind of social father who holds a ‘normative socio-economic and moral position.’ In this way a migrant worker’s son will take the place of his father once he retires. The charitable donations that the retired worker relies upon, suggests Alajmi is a form of social security. However, in spite of this set up, the remittances sent back to Yemen are irregular and sporadic. These are usually in the form of money or as food stuffs and medicine which are sent and/or taken back during festive occasions or visits. Yet the precariousness of the workers is due to their ‘visiting-feeding’ position and this means that they rely heavily upon the goodwill of their employers. Despite their difference of social positioning in comparison to other migrant workers who have arrived from other regions of the world, the Yemenis are still in a dependent and vulnerable situation.

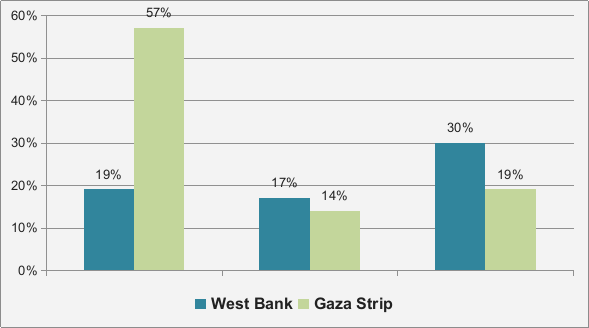

Alajmi’s concern with migrant labours travelling from Hadramawt to Kuwait is to explore possible research avenues that will enable a designing and implementation of food security policies in the region which will also address such massive social discrepancies. This is especially the case given the contrast in living conditions between the Kuwaiti employees and their labourers as well as their labourers’ kin (back in Yemen). All the more is that by 2010, Yemen was one of the countries suffering from the highest form of food insecurity. As Alajmi also points out, the relationship between the Yemeni workers and their employees is an especially complex one situated within particular interrelated notions of kinship and labour ties. Qualitative research analysis is thus essential in order to understand the ways in which state policies and legislation (and lack of) are applied and experienced within daily life. His presentation draws from his doctoral research and fieldwork and considers these employment conditions within a wider context of class-formation, labour practices and gender extending to and from Kuwaiti and Yemeni societies.

State policy and the agricultural sector: studies on Iraq, Lebanon and Egypt (25th June)

Session 4: Economic policy, the state and the agricultural sector

Kamil Mahdi, Visiting Senior Fellow, Middle East Centre, LSE – Perspectives from Iraq

Mahdi offers an historical analysis of agricultural and land tenure policies in Iraq. While the country has a deep rural culture and historic social organisation that centred around diverse agricultural activities, its engagement with the world market has been problematic for agriculture, and not least since the onset of the oil era. The current state of Iraq’s agricultural sector is evidently a ‘story of unfulfilled potential’. This is not only due to the oil rent effect, but also to the highly inequitable land rights prevalent until the reforms of the 1950s, to policies that have failed to support peasants and small farmers since, and to a reversion to land concentration from early in the 1980s.

At present, poverty are widespread among Iraq's rural population and there are serious pockets of malnutrition especially in conflict zones. The poverty is frequently associated with the country's wider food deficit, but historically and until the 1950s, rural poverty prevailed while Iraq was also a major exporter of staple crops, grains and dates. Received wisdom has it that the land reforms of 1958 and since were the cause of output decline. These ideas are experiencing a strong revival under the current neoliberal onslaught. A system with a predominantly rural population at the time, where 75% of farming households owned no land at all, and where 1% of landholders held two thirds of all agricultural land was somehow presumed more efficient than the much less inequitable peasant farm system of the immediate post-reform period. Research suggests the opposite was true, and that despite disruption and upheavals of early reform period, the reform had an overall positive effect on agricultural production.

Much is made of the fall in output in the immediate aftermath of the 1958 reforms, but that was due as much to the severe drought years of 1958-1961 as to the administrative and political chaos of the period. In fact, although the agricultural area in Iraq was reduced by a third between 1959 and 1971, output during the second half of the 1960s was at a peak. The emerging middle peasantry were able to invest in land and agricultural machinery, and they also developed a private farm service sector that rented machinery services to other farmers. This revival was short-lived and the return of the second Ba'th regime instituted the centralisation and market squeeze in the midst of the oil boom of the 1970s. The decline experienced subsequently from around the mid-1970s, was predicated upon policies of urban bias, bureaucratic centralisation, weak support, and an economic squeeze of small scale farming. By 1977, non-agricultural employment began to predominate even in rural areas. Twenty percent of rural labour was engaged in construction alone and there was a growing feminisation of farming while land ownership remained a largely male preserve. As the country was plunged into war and mass military mobilisation, the crisis of agriculture was accentuated. A policy response favouring large landholdings and capital intensive farming ensued at a time of imposed austerity and degraded state capacity. Weakened peasant and small farmer agriculture was a major reason why a subsequent policy response favouring agriculture under the early sanctions phase had limited success. Adverse trade policies since the introduction of the Food-for-Oil programme under the UNSC sanctions regime, and more acutely under US occupation, coupled with the decline in institutional effectiveness and a growing water crisis have brought the agriculture and food security situation to its present parlous state where Iraq faces a deficit in every agricultural product category-with the exception of dates. Even with regards to date production, date palms numbers have dropped from 32 million in 1960 to at most 10 million now. In dairy, poultry, sugar, cotton, as well as cereals and grains, Iraq is very highly dependent upon imports.

Session 5: Land tenure, rent and work in the agricultural sector

Elizabeth Saleh, PhD Candidate, Department of Anthropology, Goldsmiths - Neoliberal strategies and monopolisation of rent in the Bekaa

Saleh maps out the types of rent-seeking strategies deployed by urban(ized) entrepreneurs across the Kefraya region of the West Bekaa in Lebanon where most of the local residents grow wine grapes on their lands. Grapes-mainly of the Cinsault variety-were planted as early as 1949 by the ‘urban aristocrat,’ Michel de Bustros, the founder and current chairman of the Chateau Kefraya winery. These were on lands inherited from his father. In this regard there are to date, three wineries located within the municipality. These are Chateau Kefraya established in 1979, Cave Kouroum in 1998 and Chateau Marsyas (established post fieldwork in 2009). While these wineries grow their own grapes, they also rely upon sourcing grapes from the Kefraya village. This is the case also for other wineries located across the Bekaa Valley and beyond, such as Chateau Ksara. The quantities of grapes sourced from Kefraya have changed over the years as the different wineries organize new contracts with landowners in other regions of the Bekaa Valley. Nevertheless Kefraya remains an important site for wine production. Saleh presents the case of the shift during the harvest of 1996 by the largest wine producer, Chateau Ksara. The winery stopped sourcing their grapes from Kefraya and switched to other regions in the Bekaa Valley where grape varietals other than Cinsault were grown. Local grape producers in Kefraya were left with a surplus of grapes and one resident, Mr. Bassam Rahal decided to open the Cave de Kefraya winery. Tensions arose between Chateau Kefraya and the new winery; and in 1998, based upon the grounds that the Kefraya name was a licenced trademark owned by the former, Cave de Kefraya was forced to change to the name Cave Kouroum.

The presentation traces historically Kefraya’s transformation into a landscape of wine production and situates these shifts within particular forms of entrepreneurialism and types of monopoly rents. Both are linked to the laissez-faire economy in Lebanon and also in general to a global political economy of wine. Entrepreneurialism within the Lebanese wine-agro businesses is linked especially to conceptualisations of territory and place that articulate-through the notions of origins- the unique potentialities of a particular land for the production of wine grapes. The concept of ‘site monopoly’ is useful here whereby certain properties of a ‘site’ are articulated in order to promote a product’s distinctive uniqueness. Wine in this sense has the capability to highlight many dimensions of these kinds of qualities. After all it is not just the wine produced that displays distinction, uniqueness and authenticity. It is also the vineyard and the winery that become important sites of exclusivity. Here, other forms of trade, such as tourism can then be exploited. ‘Sites’ such as Kefraya therefore attract the investment of entrepreneurs seeking to gain monopoly privileges. On the other hand, competing entrepreneurs will seek to maximize their capital by developing other ‘monopoly sites’ (both within and outside of Kefraya) and are thus part of wider neoliberal expansionist projects demarcating boundaries between the rural and urban.

Raymond Bush, Professor of African Studies and Development Politics, University of Leeds (Egypt) – Perspectives from Egypt

Bush considers the fate of small scale farmers in Egypt within a broader context of the country’s political economy. Historically small scale farm production has been seen to be far more efficient than large scale production. Nevertheless, a law passed in 1992 that became fully effective in 1997, revoking earlier reforms that allowed farmers to hand down their tenancy to the next generation, worked in the interest of large land owning parliamentarians. Bush demonstrates how mass displacements of small farmers were part of a wider class struggle and conflict. The process of accumulation and dispossession and the persistence of violent practices within it reproduce a pattern occurring across wider spaces.

Agricultural strategies deployed by the pre-revolutionary Egyptian state-which were supported by USAID-focused entirely upon the control of land value. Bush argues that analytically land should be considered to be more than just a commodity with a price or value for its land-use. It should also be looked at as a territory, constructed as a kind of bio-politics, which becomes a form of political power. By doing so, the territorialisation of the land through legal reforms such as that passed in 1992 and fully effective in 1997 resulted in the abjection or marginalization of small scale tenant farmers within these new agricultural frameworks.

Since January 25th, 2011 and the escalation of protests inside Cairo’s Tahrir Square, there has also been a strong mobilisation of small-scale farmers, with over 1,500 coming from rural regions to protest in the streets of Cairo. The current Ministry of Agriculture has made attempts to address the issues stated above. The return of the cooperatives has been considered as a possibility for sustaining long term agricultural growth. This is especially interesting given that historically a lot had been done to eliminate cooperatives. The displacements from land and the development of rural enclaves have far reaching implications concerning class struggle and class formation. Bush concludes that any future research carried out with an aim of assisting in policy making, must also address issues of class dynamics. More importantly, it must look at how poverty is not simply created, but also reproduced.

Invited Participants

Abdullah Alajmi, Course Chair, Social Sciences, Arab Open University, Kuwait

Raymond Bush, Professor of African Studies and Development Politics, University of Leeds

Elizabeth Frantz, doctoral candidate, Department of Anthropology, London School of Economics

Andrew Gardner, Assistant Professor of Anthropology, Department of Comparative Sociology, University of Puget Sound, USA

Ali Kadri, Visiting Senior Fellow, Department of International Development, London School of Economics

Kamil Mahdi, Emeritus Senior Lecturer in the Economics of the Middle East, Exeter University and Visiting Senior Fellow, Middle East Centre, LSE

Dina Makram-Ebeid, doctoral candidate, Department of Anthropology, London School of Economics

Michelle Obeid, Research Fellow in Arab Diaspora, Department of Social Anthropology, University of Manchester

Frédéric Pelat, Agronomist, ONG Iddeales, Sana, Yemen - Food Systems and Natural Resources Linkages facing Socioeconomic Mutations in Yemen

Elizabeth Saleh, doctoral candidate, Department of Anthropology, Goldsmiths, University of London

Rami Zurayk, Professor of Agricultural and Food Science, Faculty of Agriculture, American University of Beirut