The New Health Insurance Law for Egyptian Farmers and Agricultural Workers: A Critical Review

Summary

On 18 September 2014, almost one week after the commemoration of Egypt’s National Farmers’ Day, Egyptian President Abdel Fatah El-Sisi issued Law No. 127 expanding health insurance to cover uninsured agricultural holders and agricultural workers. This report investigates the details of the new Law and the way in which it is being implemented on the ground. Specifically, it tracks the early phase of its execution, mainly by interviewing relevant stakeholders and conducting fieldwork in the North Giza governorate villages of Wardan, Abu Ghalib and Um Dinar between June 7 and September 30, 2016.

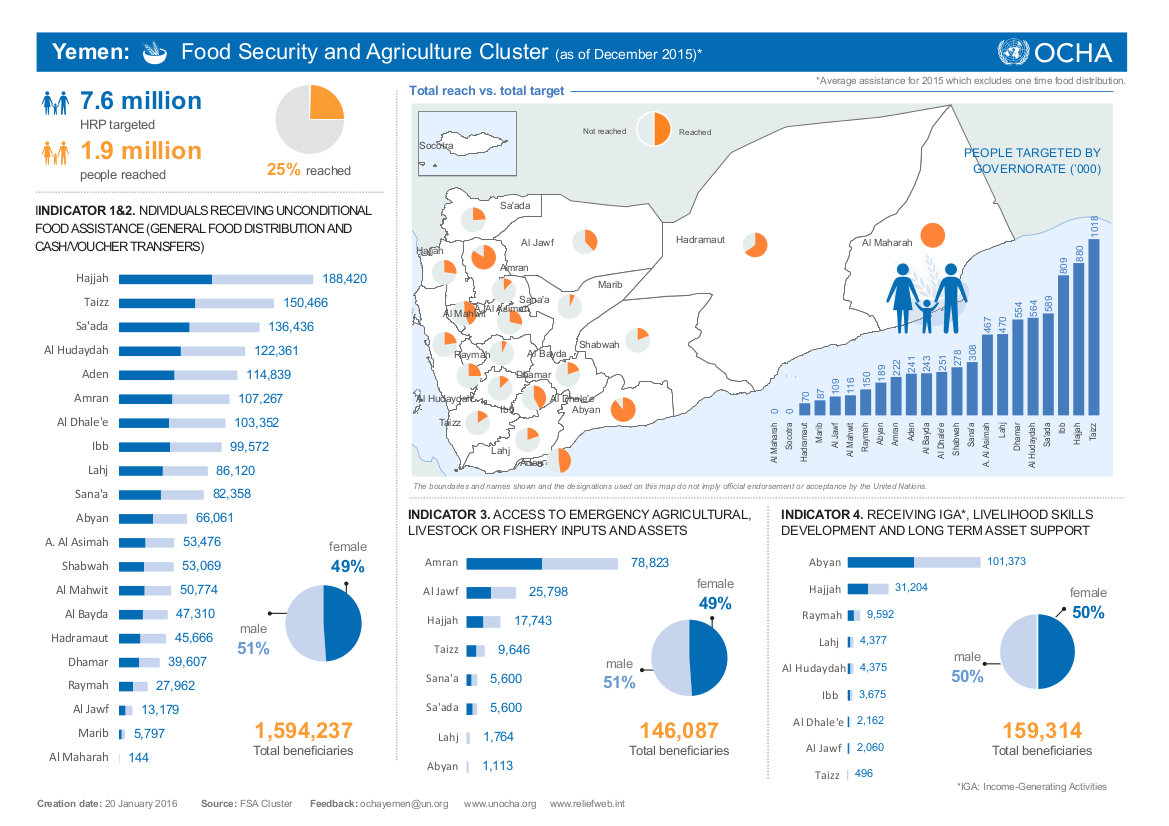

Research on which this report is based was carried out with a generous grant from the American University of Beirut under the umbrella project “Rural Well-Being: A Key to Food Security and Social Justice in the Arab World”. The grant was administered by the Social Research Centre, the American University in Cairo. Field research was conducted in partnership with the Egyptian Association for Collective Rights (EACR). It aims to provide timely documentation and nuanced analysis of the effects of newly issued health care policies affecting the well-being of Egyptian farmers and agricultural workers in the aftermath of the January 25th uprisings.

Structure of the Report

The report is broadly divided into three main parts. In the first part, after providing a historical overview of healthcare provision in Egypt and the evolvement of the health insurance system, we examine the policy process that led to the introduction of the Law. Specifically we address the specific political context within which the Law was passed in order to understand the political motives affecting its issuance. In the second part, we discuss the early phase of the new Law’s implementation in terms of coverage, outreach mechanism, financing and anticipations. In the third part, we conclude by listing a set of six recommendations for ways to move forward in allowing expected beneficiaries to benefit from the health insurance scheme, which in turn will strengthen their health rights.

Research Activities

Research activities for the research project included reviewing relevant scholarly literature and compiling grey literature, organizing a roundtable discussion, conducting in-depth interviews with policy advisers, state bureaucrats, researchers, activists and NGO practitioners with expert knowledge on the subject in Abu Ghalib, Um Dinar and Wardan. In the three villages, we primarily used qualitative methods. These methods included: direct observations, group discussions and in-depth interviews. In addition, we visited and observed daily interactions between villagers and state officials at the local health units and the agricultural cooperatives.

Challenges and Considerations

Due to the vulnerable security situation that characterized Egypt in the post-June 30th coup, the research team was extra-cautious in selecting the fieldwork sites and partners. In order to ensure the safety of the researchers and the research participants involved in the project, we partnered with the Egyptian Association for Collective Rights (EACR) and selected three villages as main sites for undertaking the research activities, namely: Um Dinar, Wardan and Abu Ghalib in North Giza governorate. We chose these villages because the EACR has been doing community-based development projects and advocacy work there for decades. Members of the EACR collaborated with us on all research activities, from beginning to end.

Another challenge that we encountered during our fieldwork was undertaking more extensive fieldwork to assess the quality of health services at local hospitals, health units and Health Insurance Organization (HIO) clinics mainly because health staff were fearful in response to a prevalent social media campaign carried out at the time criticizing the corruption of public health providers.

Findings

Several important lessons derive from this analysis concerning the benefits and applicability of the Law.

Firstly, the Law contradicts the Ministry of Health and Population’s vision of implementing universal health coverage for all Egyptian citizens regardless of their occupation or demographic statistics. However, if implemented efficiently, the main advantage for beneficiaries covered by the new Law is that they will have access to specialist and consultant doctors both in the private and public sector contracted by the HIO. This will provide some health protection for them until the instigation of the universal health insurance coverage.

Secondly, research on the cost and demand of the project was not adequately carried out to determine the feasibility of the project and its implementation by the different state bodies. As our interviews revealed, President Abdel Fatah El-Sisi passed the Law without consulting the state actors involved. This problem became exacerbated in the absence of an enforcement mechanism ensuring the execution of the Law.

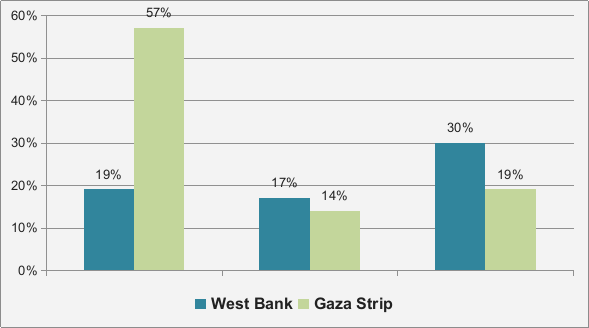

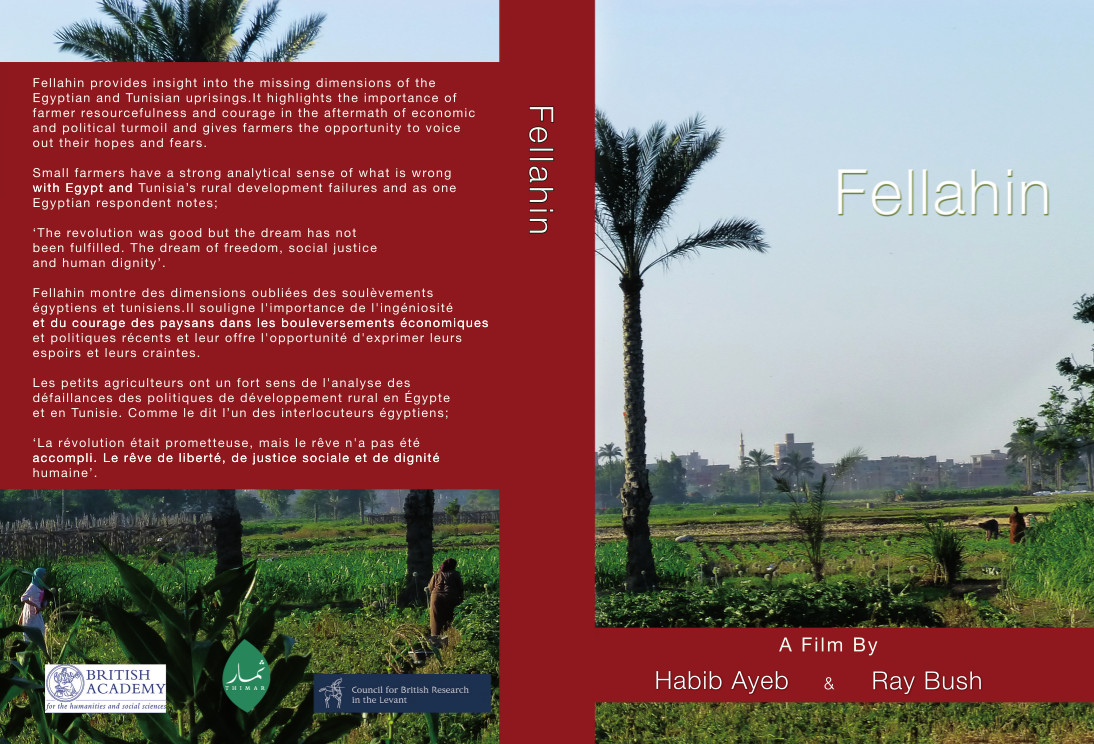

Thirdly, the mechanism used by the Egyptian government to reach out to the beneficiaries was largely limited, leading to a de-facto exclusion of women, tenants, landless farmers, sharecroppers, agricultural workers and to a lesser extent, farmers who hold university education. The word of mouth at agricultural cooperatives was the only official means for outreach of potential beneficiaries. Those who learned about the Law at the agricultural cooperatives are male landowners since they are the ones who frequent the agricultural cooperatives to receive their shares of subsidized agricultural inputs. Otherwise, eligible farmers and agricultural workers learned about the Law through farmers’ union leaders. Consequently, in villages where farmers unions are not active, tenants, sharecroppers and landless farmers were not informed about the Law. In some instances, clerks at the agricultural cooperatives sometimes exclude uninsured farmers who hold university education or technical certificates because, in their views, they do not qualify as “fellahin”. We also found that women farmers had very limited information about the Law for two main reasons. Firstly, women in the farming occupation are often landless. Secondly, women landholders do not frequent the agricultural cooperatives because the collection of agricultural inputs is often considered a male task

Fourthly, many of the beneficiaries were unaware of how to proceed in registering for the health insurance scheme whereas others were not able to provide the documentation required for registration. Moreover, those who were aware of the process were hesitant to partake in it fully for several reasons including: the high cost of the out-of-pocket premiums, their poor trust in the public health facilities at large and the Law’s limited consideration to the risk factors associated with the farming occupation.

Our findings therefore conclude that the farmers’ health insurance law, Law No. 127 of the year 2014, is mainly driven by political motives but lacks the research, finances, and consensus among the different parties to the Law, thus rendering it difficult to implement.

Recommendation

Based on the findings of this study, we have compiled a list of recommendations to address the flaws of the Law in order to cover uninsured farmers who may be in a drastic need for health insurance. These recommendations mainly require governmental efforts. They include the following:

1- Setting up a central committee for the implementation of the Law, through which representatives from all the ministries and funding bodies coordinate their joint efforts.

2- Enhancing the outreach mechanism for the insurance scheme by advertising for it not only at the agricultural cooperatives but also at the local health units and through local health guides.

3- Conducting an occupational health study that addresses the specific health risks of agricultural holders and agricultural workers, while paying specific attention to women's health needs.

4- Collecting accurate data about the number of eligible beneficiaries including tenants, sharecroppers, landless farmers and agricultural workers, to be able to measure the extent to which the Law reached its beneficiaries.

5- Consulting studies that address the predominance of agriculture as a main occupation for rural dwellers, including those who hold undergraduate degrees at universities and technical schools.

6- Establishing a national campaign to issue IDs for women farmers, agricultural workers, as having an IDs is a prerequisite to apply for the new health insurance scheme.