Investments in the agricultural sector in Morocco

Field Notes

Cynthia Gharios1 & Mohammed Mehdi2

1Graduate School Global and Area Studies Leipzig University Germany

2École Nationale d’Agriculture de Meknès

Introduction

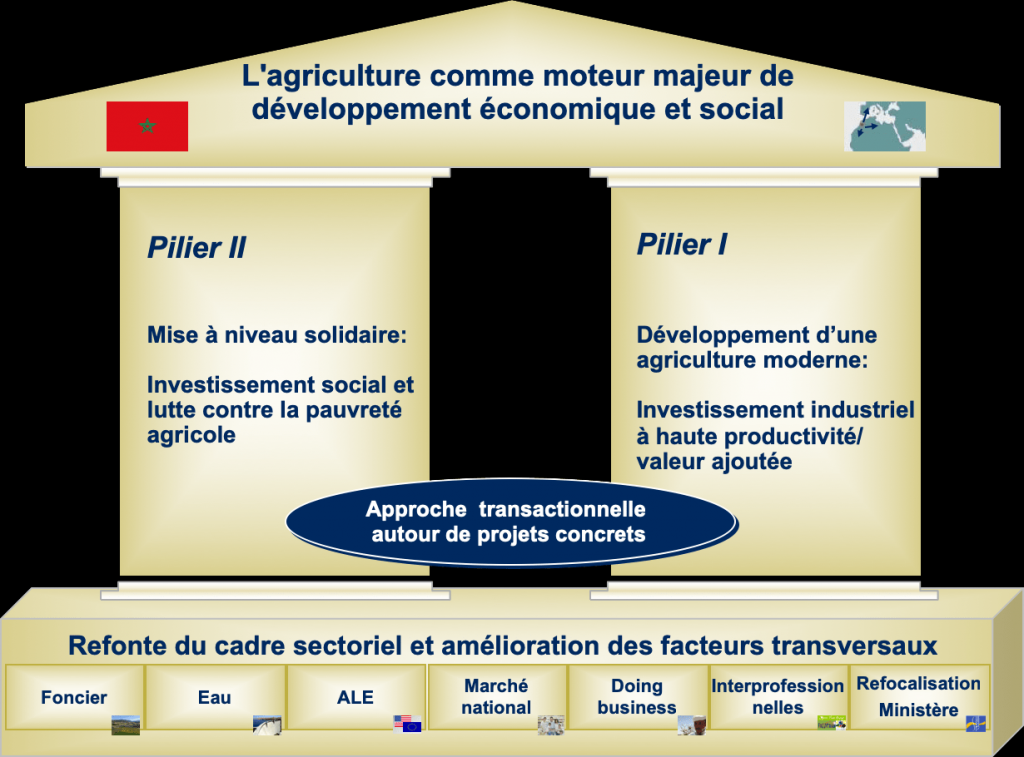

Morocco enjoys varied climatic regions and a large potential for agriculture in terms of food production. In 2017, more than 68% of Morocco’s total land area is zoned as agricultural, and the sector represents approximately 12% of the national GDP and employs 37% of the population (‘Morocco | Data’ n.d.). Since the early 2000s, following more than two decades of reduced governmental involvement (Akesbi 2006), the agricultural sector in Morocco has received renewed interest. Transformations have been shaped by changes in the land tenure structure, which allowed private players to access governmental lands as part of a public-private partnership (PPP) (Mahdi 2014). The operation paved the way for a frenzied run towards the acquisition of this state-owned agricultural land, which was attended by various actors of Moroccan and foreign nationalities, operating individually or in groups (Mahdi 2014). This was further supported by a liberal agricultural policy driven by the logic of business, gain, and profit, and formalized in a strategy of agricultural development, called "Plan Maroc Vert” (PMV). Launched in 2008, the stated objectives for the PMV are to restructure the sector in order to fully exploit the country's agricultural potential, promote investments, double the agriculture share of the GDP, fight against poverty via the creation of 1.5 million additional jobs and doubling and tripling agricultural income of 3 million rural people, encourage the protection of natural resources, support the development of partnerships between actors from the private and the public sector, and increase the value of exports from 8 to 44 Millions MAD for sectors where Morocco is competitive (‘Agence Pour Le Développement Agricole: Guide de l’investisseur Dans Le Secteur Agricole Au Maroc’, n.d., 18). This strategy is presented in the form of a "monument" with two "columns" (pillars 1 and 2), and a "base" composed of 7 transversal actions where land tenure holds an important position (see figure 1) (Akesbi 2011, 14). The first pillar focuses on the development of a modern, productivist, and export-oriented agriculture, while the second pillar aims to support what is called “agriculture solidaire’’ by protecting small family farming via three types of projects: conversion, diversification, and intensification (Mahdi 2014).

Yet these liberalisation strategies present several shortcomings. While the PMV paves the way for the development of modern productivist agriculture and an intensification of practices, it also shapes the development of new agrarian spaces and communities. We propose to focus on the models of agriculture that are being developed in relation to the nature of the PMV, the role of capital and investment in agriculture, and the imagination of the environment and sustainability that are developed. Based on empirical data from projects that benefited from the first pillar of the PMV, we highlight how the processes employed by governmental bodies, their finances, and the emerging technological possibilities are intimately linked to a rapid drive towards modernization, and are changing the notions of farming and sustainability imagination.

Figure 1: The PMV strategy. We can see in this figure the two pillars and the seven sectorial actions that would be tackled. Reference: (MAPM, n.d.)

This paper is based on a five-week fieldwork conducted in Morocco in October 2017 by Cynthia Gharios, and is complemented by Mohamed Mahdi’s extensive field knowledge. The fieldwork consisted of farm visits, interviews with a broad range of actors, and participant observation in food fairs. These were complemented by policy and document analysis, where we examined the narrative employed in the PMV and assessed its goals and objectives. Through the site visits and the discussions with the farm managers in the regions of the Saïs and Errachidiyya, we were able to study the models of agriculture being developed, focusing on issues of water and irrigation, technology and machinery, land tenure, subsidies, markets, and labour. From interviews with experts and actors in the agri-food sector in Morocco, we are able to present the perspectives of the various actors and their role in the development of new geographies of food production and imaginations of sustainability. Finally, Cynthia attended two food industry exhibitions (dedicated to olive and olive-oil production and palm dates) and two agricultural festivals for onion and apple production. Participants in these events included producers of various sizes, officials from the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Rural Development, Water and Forests (MAPM) and governmental agencies, financial bodies, as well as experts and activists. The events included platforms through which discussions about current issues and challenges took place. During her stay, Cynthia was affiliated with the École Nationale d'Agriculture de Meknès (ENAM), which granted her access to a broad network of people and companies. The interviews and discussions were conducted mainly in French and Arabic. Although a native Arabic speaker (specifically the Lebanese Arabic dialect), Cynthia found that understanding the Moroccan darija dialect was at times challenging.

The fieldwork focused on the Saïs and Errachidiyya regions. The Saïs is a plain in northern Morocco bordered by the Rif Mountains in the north and the Middle Atlas mountain chain in the south. The climate is a mix of continental Mediterranean in the winter, and hot in summer. Rainfall varies across different parts of the regions, and is generally between 300mm and 600mm per year. The region is rich in easily exploitable underground water and there are 4 dams of various sizes for irrigation, electricity production, and drinking water. The arable land area totals around 1.4 million hectares, of which 93% is irrigated, making up 15% of Morocco’s total arable area. The agricultural production is varied, comprising all kinds of cereal crops, industrial infrastructures based around sunflowers, colza and soya, leguminous produce, fruits, olives, onions, and potatoes. The province of Errachidiyya is located in the region of Drâa-Tafilalet in southeast Morocco. The region is characterised by an arid climate with very high summer temperatures (42˚C on average), and very low temperatures in the winter (-0.5˚C on average). Rainfall rarely exceeds 100mm per year, and very strong winds scour the area between May and August. The province is located over a very rich underground water basin, and around 45,500 ha are currently being developed into farming units. The main components of the local agricultures are cereals, vegetables, legumes, alfalfa, and palm trees.

The Plan Maroc Vert: A new agrarian vision for Morocco

In 2007, the newly appointed minister of agriculture tasked the strategy-consultancy firm McKinsey with generating of a new vision for the development of agricultural sector (Akesbi 2006, 2011). In a few months, the project was developed and presented at the “Salon International de l’Agriculture de Meknes” in April 2008. Designed to encourage the development of a two-fold agricultural sector with transversal activities between the two, the plan reflects on Morocco’s post-colonial agriculture division. In fact, when Morocco gained its independence in 1956, the French legacy consisted of a two-pronged approach to agriculture. One involved an export-oriented “modern” agricultural sector, open to the outside world and well-integrated into the global economy (Akesbi 2005; Davis 2006). The other was a more traditional form of agriculture, with extensive manual production and weak levels of productivity, focused mainly on internal consumption (Akesbi 2005). The PMV is updating this dualism of agriculture that has existed since the early twentieth century, while encouraging the development of common activities between the two.

In this new vision for Morocco’s agricultural sector, land and capital play an important role. The PMV is planning on providing lands through a PPP structure with an objective to develop up to 750,000ha of land up until 2020 (Mahdi 2014). It also seeks to increase investment in the sector, supported by a wide range of subsidies. The investment budget of the MAPM has tripled since 2008, reaching 75 billion MAD at the end of 2017 – of which 30 billion MAD are from donors (AgriMaroc.ma 2019). The size of private investments in the sector is estimated at 67 billion MAD by 2017 (‘Agriculture En Chiffres: 2017, Edition 2018’ 2018). In practice, the Agence pour le Développement Agricole (ADA), a governmental agency created in 2008, is responsible for implementing the government's agricultural development strategy. The ADA proposes PPP projects with renewable rental agreements over periods of 17 or 40 years. Via the web-portal of the ADA, calls-for-tenders are advertised, where relevant information concerning the project are published, including the area, the rental price in MAD per year, the type of access to water, and the category of the project. Based on the information provided, candidates prepare a project and submit the required documents, the most important of which is the business plan, which should provide a consistent project from top to bottom, with a 10-year development strategy. An important notice on personal investment from the applicant should also be included.

Access to land for farming

The development of the PMV is particularly connected with the land tenure system of Morocco. Following the independence of the country in 1953 and under the reign of Mohamed V (1957-1961), the Moroccan State began a process of recovering the lands of the official colonization (Dahir of September 26, 1963), then the lands of private colonization (Dahir March 3, 1973). These lands were estimated at around 1,000,000ha in 1956 (Pascon 1986). This did not prevent that large portions of this reclaimed land gradually passed through various real estate transactions, into the hands of private Moroccan landlords (Mahdi 2014). The recovered land consisted of the private domain of the state. Their distribution was at the heart of the issue of agrarian reform posed by the political parties of the time (Lazarev 2012). Starting in the early 1970s under the reign of King Hassan II (r. 1961-1999), these lands were indeed partially distributed as part of the agrarian reform to farmers (Mahdi and Allali 2001), while the rest was used for the constitution of state-owned companies: SOGETA, SODEA and SNDE.

With Mohamed VI taking power in 1999, further lands were liberalised. Since 2004, 120,000ha of the remaining 270,000ha of land were made available for private investors through PPP projects. These lands became part of the PMV and under the control of the ADA in 2008. However, in order to reach the 750,000ha objective, the ADA is looking for land among collective property. Indeed, the bulk of agricultural land consists of around 9 million hectares of arable land, 21.1 million hectares of permanent pasture land, and 8.8 million hectares of forest land (Mahdi 2014). While the first consists of land with various tenure juridical statuses, the others are predominantly collective property. It is therefore on these lands that PPP projects are being developed. During his speech at the opening of the legislative year on 12/10/2018, King Mohammed VI announced the enlistment of 1 Million hectares of collective lands for the realization of agricultural investment projects. This change in the land use and land tenure structure is further empowered by the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) partnership with Morocco. The project entitled “Morocco Employability and Land Compact” signed in 2015 encompasses the “Land Productivity Project”. The latter comprises three activities: 1) Governance Activity to support the development and implementation of a land governance sector strategy, 2) Rural Land Activity to convert collective irrigated land into individual ownership, and 3) Industrial Land Activity to shifting from a state to a market-driven approach by using PPP for industrial land development and management (‘Morocco Employability and Land Compact’ n.d.).

The subsidies system

Even though various subsidies existed prior to the development of the PMV, the latter has more on offer in terms of subsidies, and facilitated the process of obtaining them. Agricultural subsidies are granted and managed by the “Fond de Développement Agricoles” (FDA). Created in 1986, its aim is to promote private investment in the agricultural sector. The FDA is the instrument for the application of agricultural policy and the principal tool for investment. The FDA's agricultural incentive system was revised to align it with the objectives of the PMV (MAPMDREF 2018). The development of a “Guichet Unique” – a decentralised office where farmers can submit their application while avoiding trips to regional offices – facilitated greatly the access to funds. In a nutshell, everything needed for the development of an agricultural project can receive subsidies: the implementation of irrigation systems, required land works, the acquisition of equipment and machinery, the purchase of seeds, seedlings, plants, and animals, the building of a factory or a packing station, the export of the production, and the development of agrégation projects. For example, an investor from the first pillar can receive up to 80% of the cost for developing a ‘water-saving irrigation system’ with a cap set at 36,000MAD per equipped hectare. This rate can reach 100% when the investor proposes an agrégation project with a cap raised to 45,000MAD per equipped hectare. Investors can also receive 30% to 50% subsidies on tractors and machinery, 10% on factory building, and a subsidized fixed price per ton of product exported to specific countries.

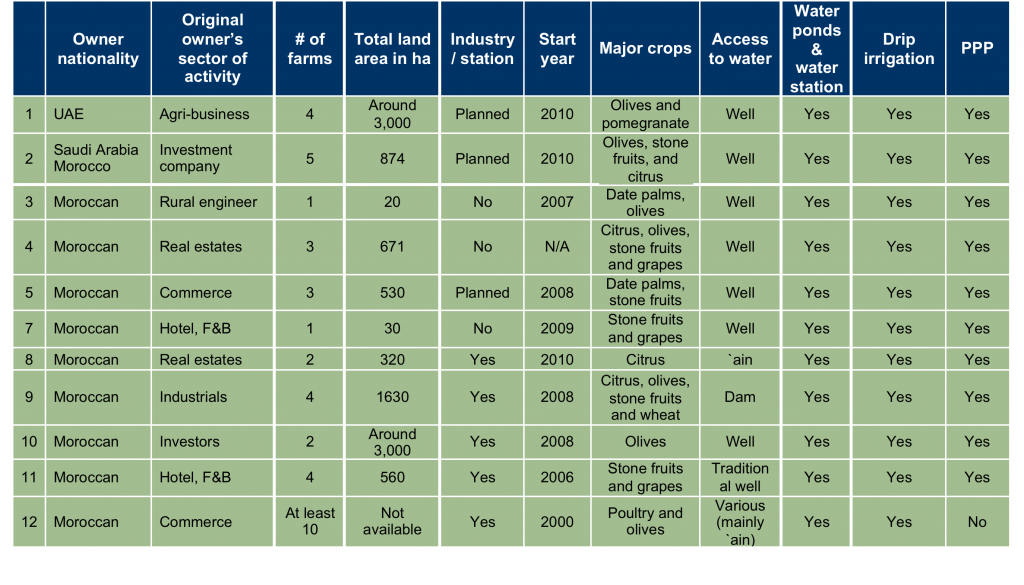

An ethnography of farms

The farms visited included a small sample of seven out of the ten production branches, namely poultry, citrus, milk, olives, fruits and vegetables, grains, and date palms. While the farms were different in many regards, several similarities were noted. Table 1 summarizes the farm visits. All except for one of the farms visited were classified as intensive farming units. The one exception was “forced” not to develop an intensive operation due to the limited availability of water. The other farms ranged from super intensive to hyper intensive plantations. This can be translated as follows:

- For olives, a super intensive plantation is planted on a grid of 4 by 1.35m; hyper intensive plantations are laid out on a grid of 3.5 by 1.2m. The latter gives roughly 2,320 olive trees per hectare, around 470 more trees than super intensive plantation.

- Date palm trees are planted on an alternate 9 by 9m grid.

- Almonds planted in hyper intensive plantations follow a grid of 3.5 by 1.5m. This allows 1,000 more trees per hectare than super intensive plantations.

- Stone fruit grids vary according to the species, but on average there are around 1,500 trees per ha.

Table 1: An outline of the visited farms

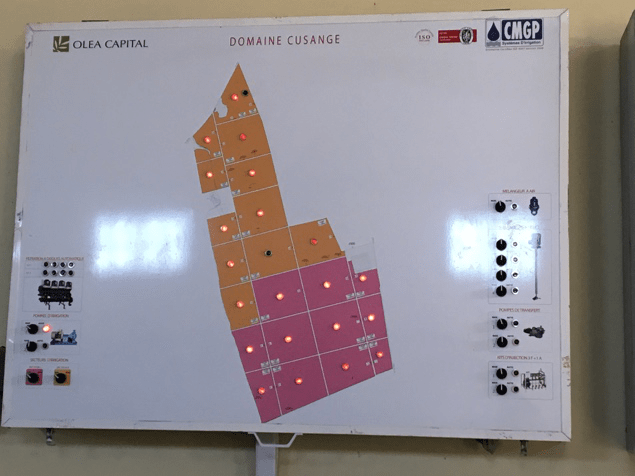

To support such intensive planting, several elements need to be respected. Firstly, the varieties chosen need to be adapted to the planting conditions. In the case of olives, for example, intensive farming is impossible using the local variety called picholine marocaine, but can be accomplished using the “Spanish varieties” of koroneiki, bosana, picual, and arbiquina. Figure 2 shows a hyper-intensively planted olive farm. Secondly this planting scheme facilitates the development of mechanised harvest although increased care should be taken with the trees (such as for pruning) in order to use mechanised systems as efficiently as possible alongside the application of fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides in order to obtain the “best quality olives”. An example of the mechanisation is seen in figure 3 for a multi-functional tractor. Thirdly, such intensive plantations demand larger quantities of water. In the majority of the farms visited, water was provided from wells. In the Saïs, the well depth varied between 60m and 80m for a modern well and 30m to 40m for traditional wells, while in Errachidiyya the depth of the wells is 130m to 150m. Some farms had a right to or ownership of an `ain (or water source). Regardless of the nature of access to water, all farms have one or more ponds with sizes varying between 5,000m3 for a 20ha plot of land, to 60,000m3 for a 300ha plot of land. The ponds are typically linked to an irrigation station where the quality of water is monitored and fertilisers are added before the water is distributed in smaller parcels via drip irrigation. The system is fully automated and monitored by computers – see figures 4 and 5 regarding the water system. While the system is supposed to use less water per hectare, trees often end up being over-irrigated. A water expert stated:

Farmers are reluctant to use local research as a reference point, but rely on research conducted in California, where the conditions are different to those in Morocco. Therefore, they sometime irrigate four times more than what the plant needs.

The commercialisation of the production was an important part of our discussions with farm managers. When asked, all farmers confirmed that production was aimed at the local market. However, they all expressed frustrations about access to international markets. In a few cases farm managers proudly displayed their Global GAP certification – an EU norm, required in order to sell fresh produce in European retail chains. Therefore, the farmers’ desire to export their produce was clear. The main criticism addressed to the PMV is to have concentrated the effort on the production side of agriculture, while neglecting aspects of valorisation and especially that of marketing.

Figure 2: a hyper-intensive olive farm in the Saïs (Photography taken by C. Gharios 2017)

Figure 3: Pellenc 8590, is owned by an olive farm in the region of the Saïs. The machine can harvest up to 1ha per hour (around 16ha per day) while at the same time separating the fruits from the wood so that one can skip a step at the factory. It can also be used for applying phytosanitary treatments or any leaf or air straying treatment, and can cover up to 40ha per day (Photography taken by C. Gharios 2017)

Figure 4: A water pond where the water is kept after being either pumped from the well or received by the canalisation of a dam (Photography taken by C. Gharios 2017).

Figure 5: A water station system. The blue reservoir filters the water, while ones in the background (in white) are filled with fertilisers or other treatments to be applied with the irrigation system. The manager of the farm activates and controls the irrigation via this board (top image). (Photography taken by C. Gharios 2017)

All the owners of the farms we visited developed their agricultural business starting in the mid-2000s, as a side-line. Owners included one industrial group, two real estate companies, one trade company specialising in household appliances and another in egg distribution, two companies working in the food and beverage sector (restaurants and hotels), and three investment bodies. Although meetings with the owners did not take place, the managers explained that companies and wealthy individuals had been encouraged to invest in agriculture in order to diversify their portfolio of businesses and generate profits from different sources. Two owners had a slightly different background. One was an agricultural engineer who had access to land near the city of Fez following agrarian reform in the 1970s. However, the urban area around Fez expanded and his land gained value for real-estate purposes. He decided to sell the land for urban development and buy a larger plot (30ha) for agriculture further away from the city. At the same time, he developed a restaurant business in Fez. The other was a rural engineer who had worked in a government agency for 30 years in Errachidiyya. He had always dreamed of one day owning a small parcel of land and cultivating it. Due to the advantages offered by the PMV offers, he was able to access a plot of 20ha for the development of palm trees. His plan is to develop a farm as a retirement project. All these farms have relied on land subsidies via the first pillar of the PMV. The farms visited in the Saïs region used to be colonial farms that were later taken over by SOGETA and SODETA. The farms visited in Errachidiyya were originally collective land that had traditionally been used for pastoral activities.

Discussion

According to official reports, a general boost in Morocco’s agricultural production has been observed since the development of the PMV. The agricultural GDP has increased from 65 billion MAD in 2007 to 111 billion MAD in 2016, while areas using the drip irrigation system have tripled, and agricultural exports increased from 15.2 billion MAD in 2008 to 21.3 billion MAD in 2016 (“ADA - Agence pour le Développement Agricole” n.d.). Morocco’s total agricultural area reached 8.7million hectares in 2016, of which 52% are used for cereal production, 20% are fallow, and 28% are planted with various crops. This, according to the MAPM, offers further great potential for intensification and reconversion to high return crops (‘Agriculture En Chiffres: 2016, Edition 2017’ 2017). While it is clear that the PMV has set in motion the transformation and development of the agricultural sector in Morocco, the strategies used present several shortcomings. The PMV has paved the way for the development of modern productivist agriculture and an intensification of practices – which raises the question of its environmental impact. At the same time, it has shaped the development of new agrarian spaces and communities.

The gold rush for agricultural investments

The PMV has acted as a driver for investment, inviting people from different sectors and nationalities to invest in the agricultural sector. The opportunity to develop successful projects and the potential for high return on investment are encouraging real estate agents and trade companies to enter this sector. Under the slogan of business diversification, new landlords are keen to realise quick profits and develop agro-industrial operations within their portfolio of businesses, building these operations up further for landlords who are already involved in the sector. The new class of farm-investors benefits from state subsidies that often reach 80% of total capital expenditure, and from easy access to long-term rental agreements on very large parcels of land. New farms tend to boast high-tech agricultural systems, with water-saving technologies, with the usage of fertilisers and pesticides resulting in high quality produce suitable for export. The availability of subsidies and the ease of obtaining them encourage investors to develop high-tech farming systems that they could not otherwise afford. The limited absolute sum that is being asked of investors and the extensive subsidy system allows for very limited risk, and an almost guaranteed profit – at the expense of government finances.

The new landlords tend to be absent from their properties, and are usually based in the large cities of Rabat and Casablanca, or even in other countries. They tend to visit their farms on average 2-3 times a year, and generally delegate their management to the agricultural engineer or technician who lives on the land. This gold rush for agricultural investments and land highlights the positive branding created by the government toward agriculture as a revitalised economic sector. While praise for the PMV dominates governmental discourse, the reality on the ground is less sanguine. The success of production is not met with proper commercialisation. The promise of available markets is not being kept. Fruits and vegetables are regularly rejected for non-conformity in terms of international norms. Furthermore in 2017, a large portion of the trees planted since the beginning of the PMV had not yet reached maturity. For example, the overproduction of clementine in 2018 led to unusually low prices of this fruit, especially for the farmer (Guennouni 2017) This raises the question of what will happen when the farms reach their maximum productivity. Is commercialisation the forgotten aspect of the PMV? Is this “gold rush” for agricultural investment fuelled by “free money” justified by the actual demand for the products?

Spatial transformation and environmental impact

From a spatial perspective, the development of high-tech farming systems encouraged by the PMV, has had a tremendous impact on the agrarian landscapes in several regions in Morocco. In al-Gharb and Meknès, new intensive plantations are replacing existing ones. Vineyards, olive groves, and rain-fed wheat fields are gradually being erased and replaced with citrus orchards and industrialized olive farms. In Errachidiyya, very small palm trees are being encouraged to grow in a desert space previously given over to pastoral activities. The development of enclosures emphasizes the disconnection between these developments and the outside world. The gated farms seem disconnected from the surrounding spaces, from society, and from the environment. Indeed, the environmental impact of intensive agriculture is enormous. On one hand, we observed an overuse of the scarce water resources where wells (both traditional and drilled) have to be dug deeper every year. This is accompanied by a slow decline in rainfall, which is not refilling superficial water tables as quickly as the water is being pumped out. Smaller farms neighbouring these new ones are suffering from the lack of water due to the intensive use from new farm-investors. The latter have this year considered increasing the depth of their wells. While one might argue that modern techniques provide high yield with limited use of water, the development of 750,000ha of potentially entirely irrigated surface renders water efficiency doubtful. On the other hand, the excessive use of pesticides is increasing the pest resistance on it, while the excessive use of fertilizer is increasing soil salinity and polluting both the soil and the underground water. Water is a key element for securing good quality of production. Yet its scarcity is reflected in the failure of farms to perform as desired. Here again, the development of the PMV and the vision of increasing irrigated land are disconnected from the development of rational water policies and the actual availability of water. It becomes important to ask whether these farms will be doomed to fail when the water runs out or irrigation becomes increasingly expensive.

Conclusion: state, nature, and capital

The PMV has been a driver for investment, inviting people from different sectors and nationalities to invest in the agricultural sector. The opportunity for developing successful projects, as well as the potentially high return on investment, are encouraging real estate agents and trade companies to enter this sector. Under the slogan of business diversification, the new landlords are keen on quick profit-making.

But this project is far from being unique. Since the early 2000s Morocco has embarked on a series of structural reforms aimed at “achieving strong and sustainable growth” (‘Agence Pour Le Développement Agricole: Guide de l’investisseur Dans Le Secteur Agricole Au Maroc’, n.d., 5). We observe changes at the political economy of the country with a liberalization of the financial sector, a restructuring of public finances, an improvement of infrastructure, and reforms of macroeconomic policies (‘Agence Pour Le Développement Agricole: Guide de l’investisseur Dans Le Secteur Agricole Au Maroc’, n.d., 5), accompanied by the elaboration of several sectoral plans that target the development of each sector individually. These included plans such as Plan Azur for tourism, Rawaj-vision 2020 for trade, Plan Maroc Numérique for the development of new information and communication technologies, Plan Émergence 2020 for industry, Plan Halieutis for fishery, and Maroc Export Plus for the development of export. Akesbi (2011) states that all of these projects were developed under the same conditions and with the same state of mind, and thus they suffer from almost the same flaws and lend themselves to the same criticisms.

The gold rush for agricultural investments and land highlights the positive branding created by the government toward agriculture as a strong economic sector. However, farming techniques, species of plants used, and the ultra-productivist agricultural model all underline important flaws. The preponderance of a capitalist development, dominated by a mere objective of maximization of return on investment, and liberalization strategies have transformed the nature of farming, and the ecosystems on which farming is grounded.

Acknowledgments:

This fieldwork was funded by the Leverhulme Trust International Network Grant (project title: Agricultural Transformation and Agrarian Questions in the Arab World).

Cynthia Gharios is grateful to the Ecole National d’Agriculture de Meknès where she was hosted and which provided access to the numerous contacts.

Bibliography

ADA. 2017. ‘L’agriculture En Chiffres 2016’.

‘ADA - Agence Pour Le Développement Agricole’. n.d. Accessed 13 March 2018. http://www.ada.gov.ma/.

‘Agence Pour Le Développement Agricole: Guide de l’investisseur Dans Le Secteur Agricole Au Maroc’. n.d.

‘Agriculture En Chiffres: 2017, Edition 2018’. 2018. Annual reports. Maroc.

AgriMaroc.ma. 2019. ‘Plan Maroc Vert: 75 milliards de DH d’investissements publics depuis 2008’. AgriMaroc.ma. 4 March 2019. http://www.agrimaroc.ma/plan-maroc-vert-investissements/.

Akesbi, Najib. 2005. ‘Évolution et perspectives de l’agriculture marocaine’.

———. 2006. ‘Evolution et perspectives de l’agriculture marocaine’. In 50 ans de développement humain au Maroc, perspectives 2025 : rapports thématiques, 85–198. Cinquante ans de Développement Humain au Maroc.

———. 2011. ‘Le Plan Maroc Vert : Une Analyse Critique’. In Questions d’économie Marocaine. Maroc: Presses Universitaires du Marco.

Davis, Diana K. 2006. ‘Neoliberalism, Environmentalism, and Agricultural Restructuring in Morocco’. The Geographical Journal 172 (2): 88–105.

Guennouni, Abdelmoumen. 2017. ‘Agrumes : Surproduction-commercialisation’. Agriculture du Maghreb (blog). 16 June 2017. http://www.agri-mag.com/2017/06/agrumes-surproduction-commercialisation/.

Lazarev, G. 2012. ‘politiques agraires au Maroc, 1956-2006. Une temoignage engage’. Economie Critique (Morocco). http://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=XF2015000018.

Mahdi, Mohamed. 2014. ‘Devenir Du Foncier Agricole Au Maroc. Un Cas d’accaparement Des Terres.’ New Mediterranean 13 (4): 2–10.

Mahdi, Mohamed, and Khalil Allali. 2001. ‘Les Coopératives de La Réforme Agraire Trente Ans Après.’ Bulletin Économique et Social Du Maroc 160.

MAPM. n.d. ‘Plan Maroc Vert’. PPT.

MAPMDREF. 2018. ‘Fonds de Développment Agricole: Les Aides Financières de l’État Pour La Promotion Des Investissements Agricoles’.

‘Morocco | Data’. n.d. Accessed 12 February 2018. https://data.worldbank.org/country/morocco.

‘Morocco Employability and Land Compact’. n.d. Millennium Challenge Corporation. Accessed 4 April 2019. https://www.mcc.gov/where-we-work/program/morocco-employability-and-land-compact.

Pascon, Paul. 1986. Capitalism and Agriculture in the Haouz of Marrakesh. Edited by John R. Hall. Translated by Edwin Vaughan and Veronique Ingman. London ; New York : New York, NY, USA: KPI ; Distributed by Routledge & Kegan Paul, Methuen Inc.